Nearly two years after the devastating Beirut port explosion that killed over 200 people, Lebanon’s ruling political class have refreshed their attempts to be seen as responding to demands for truth and accountability. On July 26, parliament elected seven members to the Supreme Council, the country’s highest possible court, which has the constitutional power to judge ministers, the prime minister and even the president.

However, despite the lofty title and decades of potential abuses of power by Lebanon’s political elite, the Council has never actually convicted anyone. It was called into action only twice since 1990: first against then-President Amin Gemayel and later against former Oil and Industry Minister Shahi Barsoumian. Neither was convicted. In 2019, there was furthermore a failed attempt to refer three former ministers to the Supreme Council on corruption charges.

Now, the Council’s latest case could be the 2020 Beirut port explosion. Could be for the Council has not yet been officially tasked with the case, and may very well never be, given the need for a two-thirds parliamentary majority to prosecute the country’s highest public officials.

While seemingly playing an all-important role in the country’s legal system, the practicalities regarding the Council reveal it to be one of the earliest manifestations of a phenomenon the Lebanese political class has turned into a true art form: reforms that look great on paper yet remain hamstrung by gatekeeper clauses preventing them from ever being implemented.

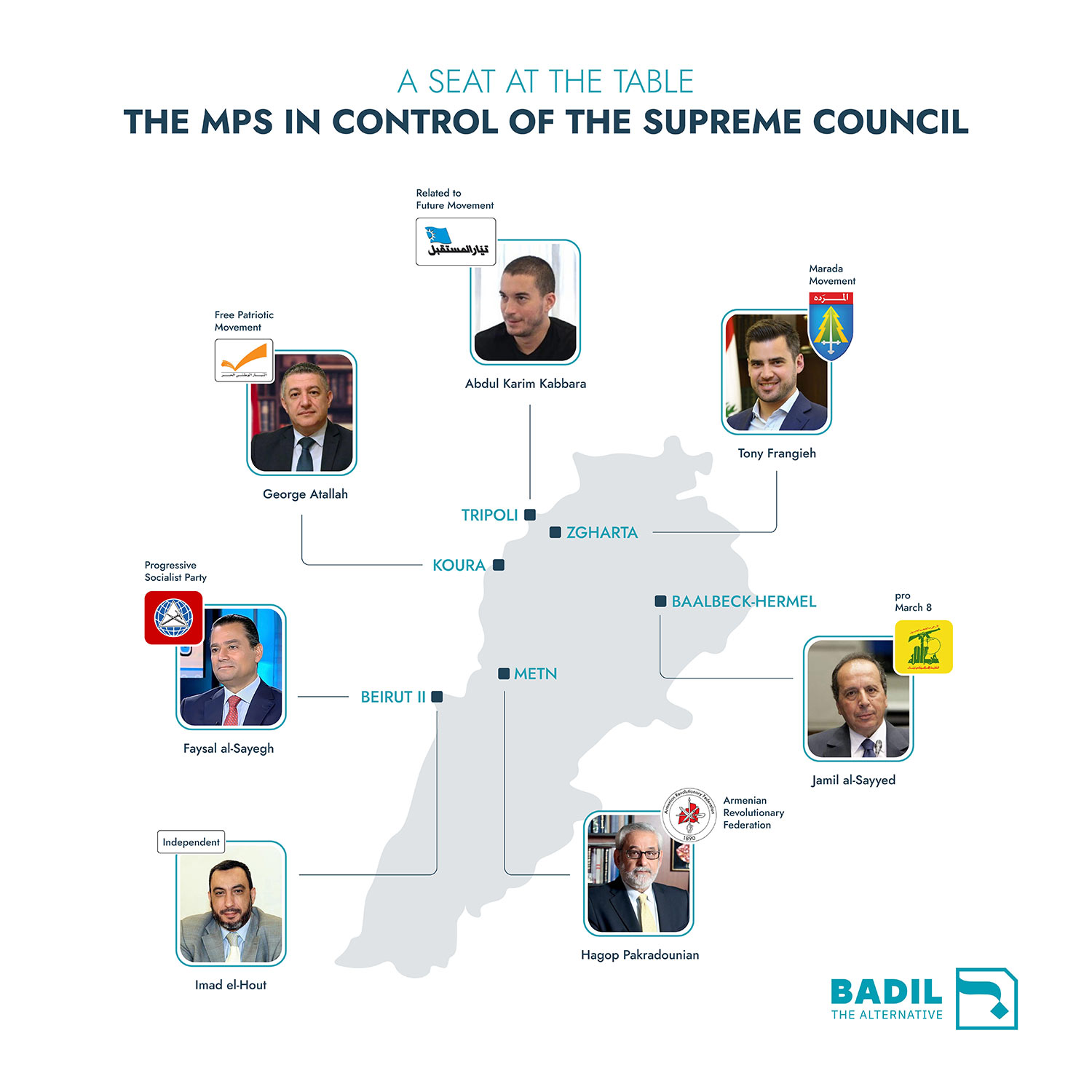

Even if the parliament tasks the Council with investigating the Beirut port blast, its composition – seven politically aligned MPs and eight judges who could be politically compromised – gives little reason for hope there will be any rigorous pursuit of justice. The seven MPs recently elected to sit at the court represent an even spectrum of stalwarts among Lebanon’s confessional system.