Haven No More

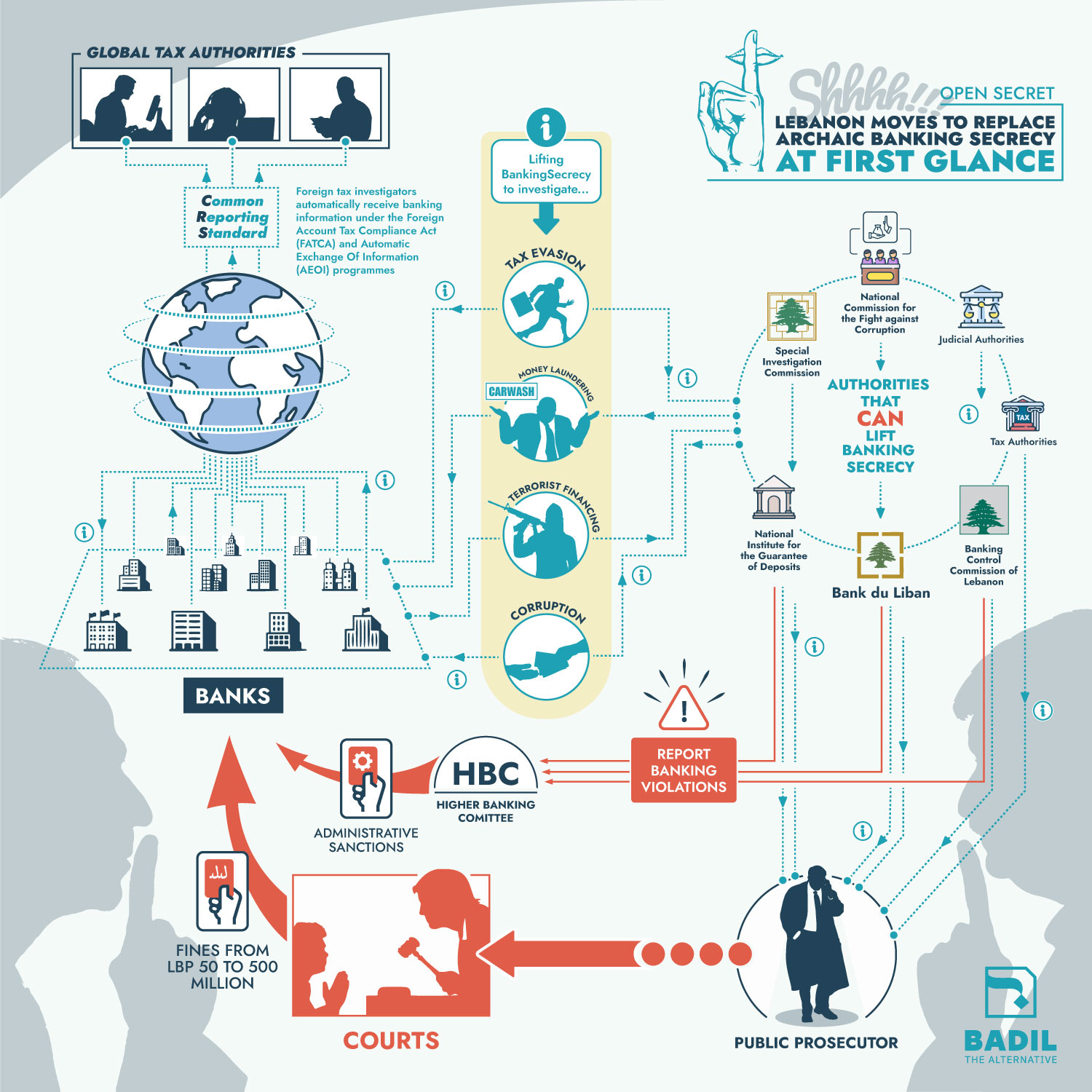

No doubt the spirit of the draft bill to lift banking secrecy focuses first on curtailing domestic tax evasion. While Lebanon complies with several international regulations regarding tax evasion, it does not uphold the same standards for its own residents.

In July 2014, Lebanon was forced to abide by America’s Foreign Account Tax Compliance Act (FATCA), which requires the country’s financial institutions to report to the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) US citizens with accounts above $50,000.

In 2018, Lebanon joined the Common Reporting Standard (CRS) developed by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), which requires financial institutions to determine a client’s main tax residence and share banking information.

However, CRS and FATCA apply to accounts held by foreign tax residents, who generally stem from the global north. Meanwhile, it is estimated that the Lebanese government loses up to 49% of annual revenue due to domestic tax evasion.[6] Rather than implementing new regressive taxes, as it has done in the past, Lebanon must find a way of collecting the estimated US$5 billion in uncollected taxes every year.[7]

To support better tax collection, the draft bill tasks the Director General of Revenue at the Ministry of Finance with defining “the bases, standards, and mechanisms for accessing information protected by banking secrecy, the scope of disclosure, as well as the necessary guarantees.” Lebanon’s tax authorities may request “any information required” to carry out their duties, without having to go through the SIC.

The draft bill also offers legal authorities, including investigating judges, the prosecutor at the Court of Cassation, and the judicial police, access to banking information in order to fight money laundering and terrorist financing.

The bill thereby bans the use of numbered accounts and safety deposit boxes. Under the draft legislation, these accounts of which the owners’ names are concealed, will be converted to nominated accounts and subject to the same conditions of the law. By lifting banking secrecy for judicial authorities and banning numbered accounts, reprehensible financial practices will be discouraged.

Commissions, commissions

Founded in 2020, the NACC can also request to lift banking secrecy regarding account holders’ names, amounts and safety deposit boxes. The anti-corruption commission has the herculean task to investigate violations to laws regarding the right of access to information (2017), whistleblower protection (2018), hydrocarbon sector transparency (2018), illicit enrichment (2020), and public procurement (2021).[8] Yet, to date, most of this legislation has not been put into practice.

Decisions to investigate will be taken by a majority of its members, four of whom were appointed by the cabinet.[9]

The National Institute for the Guarantee of Deposits can also request access to banking information. The rather obscure institute to safeguard deposits was formed in tandem with the BCC and the Higher Banking Commission (HBC) to restore confidence in the Lebanese banking sector as a result of the financial crisis caused by the 1967 Six-Day War.

Established as a cooperative joint stock company, with banks participating in half of the capital and the government in the other half, NIGD did so at the time by guaranteeing deposits in Lebanese Pounds (LBP). The body works closely with the Association of Banks in Lebanon (ABL), which elects four of the seven board members, while the government appoints the remaining three.

Stunningly, the draft bill does not stipulate the conditions under which NIGD can file a request for information. It only states that the NIGD Board of Directors may request information for customers who “meet certain criteria,” yet fails to define what they are.[10]

Given the bill’s objective to investigate illicit financial activities, it is not clear why the government would allow an institution with such close ties to the banking industry to investigate that same industry. Nor is it clear why NIGD would need to access banking information in the first place.

The Power to Abuse

While a promising step to fight financial crime, corruption and tax evasion, the draft bill is characterized by glaring loopholes that open the door to abuse of power. For example, BDL, BCC and NIGD must report banking violations to the Higher Banking Commission (HBC), which is to then take the “necessary legal measures” against banks. However, it fails to define what these measures are.

Worse, doubt swirls over all three institutions. BDL governor Riad Salameh is today considered the architect of Lebanon’s financial collapse and faces corruption and embezzlement charges in several countries. The BCC is another comprised institution, as one board member is always appointed by the ABL, which also appoints most NIDG board members.

The HBC can also introduce “administrative sanctions” against banks. However, yet again, four of the five current HBC board members are closely tied to the banking industry. They include BDL Governor Riad Salameh, the BDL’s Third Vice-Governor Salim Chahine, Director General at the Ministry of Finance Khater Abi-Habib, and a NIGD Chairman (ABL compromised) and a BCC member.

That is not all. The draft bill amended what used to be a prison sentence of three months to a year for banking violations to a fine of LBP 50 to 500 million. According to the current informal exchange rate, this amounts to some US$1,600 to US$16,000. For banks protecting a wealthy client or politically exposed persons, that is peanuts.

Arguably the hole among holes is allowing banks to reject requests from the authorized authorities, given the rejection is in writing and includes a justification. That is all. The bill does not stipulate any criteria that must be met to justify such a rejection.

Timid Steps

Still, not so very long ago a draft bill of this magnitude would have been dead upon arrival. These days it is at least discussed in parliament. While it is unlikely that the first draft will be accepted without amendments, the proposal represents a timid step forward in reforming Lebanon’s once untouchable banking sector.

There is little doubt that the lifting of banking secrecy would help restore international confidence Lebanon needs to cajole other countries and institutions to join the IMF’s rescue plan, as the Fund envisions. Yet if the current draft banking secrecy law is anything to go by, no one should be fooled into thinking the vault is about to crack open just yet.