Raising the stakes

Perhaps more than ever, Lebanon’s political leaders have a strong incentive to prevail in the upcoming parliamentary elections. The country has reached a “staff-level agreement” with the International Monetary Fund (IMF) for a financial rescue package, which politicians hope will lead the nation out of its unprecedented economic crisis.

“There is an urgency to unlock the IMF loan and the recovery packages,” political researcher Nadim El Kak told The Alternative. “Holding these elections is the way for this traditional political class to reassert its legitimacy.”

The EU Election Observation Mission’s presence can help those same leaders to avoid accusations of holding unfair elections, as they have done before.

“If [sectarian leaders] can prove that [they] held elections that had international monitoring […] that gives them the legitimacy they need to negotiate with foreign actors and speak on behalf of the people,” said El Kak.

Indeed, it was Lebanon’s Ministry of Interior and Municipalities that invited the EU Election Observation Mission to watch over this year’s parliamentary polls.

Little to fear

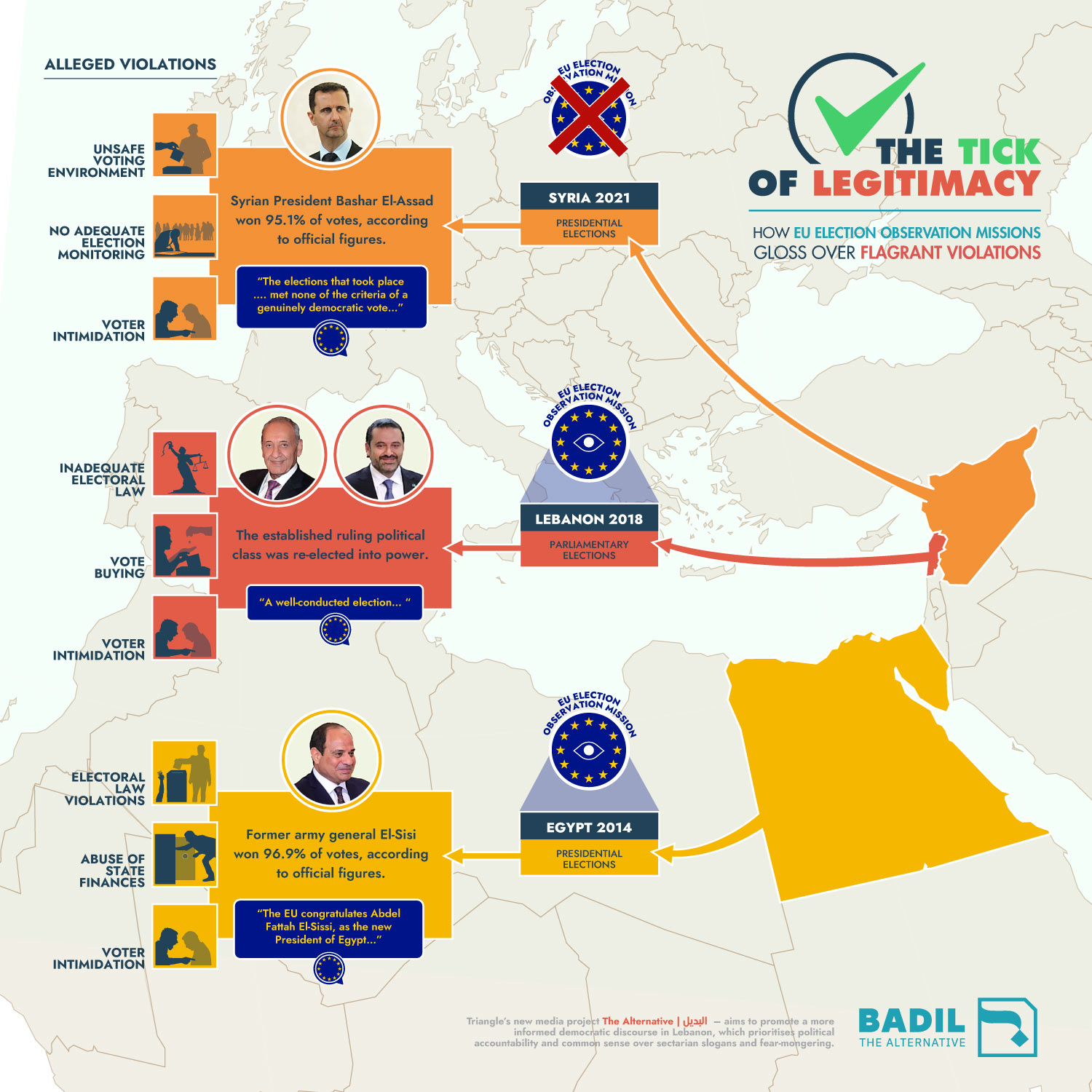

The ministry’s openness to international monitoring reveals the political class’ confidence that such missions rarely lead to serious condemnation. In fact, the Lebanese government invited a European election observation mission to oversee the nation’s 2018 parliamentary elections – polls that witnessed alarming interference.

El Kak, a former member of the opposition party Li Haqqi, highlighted the use of makanats, or institutional machines, to intimidate voters during the last election.

According to El Kak, sectarian party representatives kept track of the order of families as they entered voting centres. Based on this surveillance, parties could later identify which families had defected during the vote count.

This tactic effectively instilled fear in voters of social and financial repercussions if they voted against their local establishment party.[4] Such considerations matter in Lebanon, where many citizens rely on access to corrupt patronage networks to sustain their livelihoods and basic living standards.

Voter intimidation was far from the only form of interference in the 2018 parliamentary elections. Before the polls, Lebanon passed a widely criticised electoral law, which unfairly advantaged the country’s established sectarian parties.[5] The election was also rife with allegations of establishment parties paying constituents for their votes.

Despite these factors, the EU observation mission’s 2018 report heavily downplayed vote-buying and did not mention voter intimidation.[6] One of the mission’s main recommendations revolved around increasing women’s participation in Lebanese political life, suggesting a quota for women on candidate lists at future elections.[7]

Lebanon’s sectarian parties did not heed the observation report’s advice to institute a quota system. In 2018, females constituted just 14.4% of overall parliamentary candidates. This year, 155 women are seeking legislative office – about 15% of the field.[8]

Legitimising the illegitimate

Political scientist Karim Bitar agrees that – far from dissuading sectarian parties from engaging in dirty tactics – the EU Election Observation Mission can confer a sense of propriety on unfair elections.

“When it comes to the international community, they will be able to tell the various ambassadors: We have held the elections on time, you know the rules, you sent observers, the observers didn’t see massive cheating on the day of the elections,” he said.

For Bitar, projects like the EU Election Observation Mission tend to adopt a narrow focus when checking for violations. “They don’t see anything wrong on the day that they are present in Lebanon,” he argued. “It’s not on the day of the elections that the cheating takes place.”

The EU Election Observation Mission’s 2018 performance forms part of a broader dilemma for monitoring projects worldwide. Susan D. Hyde, a political science professor at the University of California, Berkeley, contends that pseudo-democrats rely on supposed election watchdogs to legitimise flawed polls.

“The possibility that observers will not condemn a manipulated election is a central reason why pseudo-democrats are willing to invite them in the first place,” Hyde wrote.[9]

Aside from Lebanon’s 2018 parliamentary elections, EU observation missions have played a similarly benign observation role amidst accusations of rampant violations. In 2014, EU representatives observed Egypt’s presidential elections, which former army general Abdel Fattah El Sisi won by a truly incredible 96.9% of total votes.

Days after the election, the EU’s observation mission released a preliminary assessment that indicated that several factors had compromised the election, including insufficient regulation of campaign financing. Nevertheless, the European Union officially congratulated El Sisi on his victory a week after the vote, conferring international recognition on his regime.

Indeed, the European Union has been more inclined to criticise a flawed election when no observation mission is present. Last year, Syrian dictator Bashar El Assad held presidential elections, in which he secured 95.1% of total votes (according to official figures). Allegations abounded that the El Assad regime had threatened and intimidated voters.

Unlike Lebanon and Egypt, El Assad did not invite the European Union to observe the election. Nevertheless, EU High Representative Josep Borrell issued a statement after the polls, saying: “The elections […] met none of the criteria of a genuinely democratic vote.”[10]

The European Union faced lower stakes in condemning Syria’s presidential election result, having terminated diplomatic relations with the Assad regime a decade ago. By contrast, European countries maintain strong economic ties to El Sisi’s regime in Egypt, including through trade in weapons and natural gas.[11]

Both the European Council and the European Union Delegation to Lebanon declined requests for comment for this article.

Time to get serious

With sanctions and observers in place, the European Union has positioned itself as the lead guarantor for Lebanon’s parliamentary elections.

The EU Election Observation Mission enjoys far greater human and financial resources than Lebanon’s own election watchdog, the Supervisory Commission for Elections (SCE). Underfunded and politically compromised, the commission’s president himself dismissed the SCE’s work as a “box-ticking exercise.”

In his recent Beirut press conference, EU mission head Holvenyi made clear that his observation team would not attempt to validate the election results. Nevertheless, European politicians are not constrained by the EU Election Observation Mission’s terms of reference.

In theory, EU officials could adduce evidence of electoral violations – including any incidents identified by electoral observers – as grounds for enlivening sanctions against offending parties. It remains to be seen, however, if they will use this powerful tool.

Repeatedly, the European Union has publicly declared the need to force Lebanon’s intransigent political elites to adopt genuine reforms, including delivering a more robust democratic process. For decades now, appeals to sectarian leaders’ patriotism and sense of duty have fallen on deaf ears. However, the credible threat of asset freezes and travel bans might well do the trick.

[1] European Union, 2022, “Lebanon: the European Union deploys an Election Observation Mission”, online at: https://www.eeas.europa.eu/eeas/lebanon-european-union-deploys-election-observation-mission_en

[2] L’Orient Today, 2022, “Aoun receives head of EU elections observation mission”, online at: https://today.lorientlejour.com/article/1296140/aoun-receives-head-of-eu-elections-observation-mission.html

[3] Handbook for European Union Election Observation Missions, online at: https://eeas.europa.eu/archives/docs/eueom/pdf/handbook-eueom_en.pdf

[4] Nadim El Kak, 2019, “A Path for Political Change in Lebanon? Lessons and Narratives from the 2018 Elections”, Arab Reform Initiative, online at: https://www.arab-reform.net/publication/a-path-for-political-change-in-lebanon-lessons-and-narratives-from-the-2018-elections/

[5] Sarah Ludwick, 2021, “Lebanon’s Parliamentary Elections: High Stakes Amid Crisis”, The Tahrir Institute for Middle East Policy, online at: https://timep.org/explainers/lebanons-parliamentary-elections-high-stakes-amid-crisis/

[6] Final report of the European Union Election Observation Mission to the Republic of Lebanon 2018, online at: http://www.eods.eu/library/final_report_eu_eom_lebanon_2018_english_17_july_2018.pdf

[7] Ibid.

[8] L’Orient Today, 2022, “Candidate filing period ends with 1,043 having thrown their names in the hat”, online at: https://today.lorientlejour.com/article/1293816/candidate-filing-period-ends-with-1043-having-thrown-their-names-in-the-hat.html

[9] Susan D. Hyde, The Pseudo-Democrat’s Dilemma: Why Election Observation Became an International Norm, “Does Election Monitoring Matter?”, Cornell University Press, p 127.

[10] European Union, 2021, “Syria: Statement by the High Representative Josep Borrell on the presidential elections”, online at: https://www.eeas.europa.eu/eeas/syria-statement-high-representative-josep-borrell-presidential-elections_en

[11] TIMEP, 2018, “TIMEP Brief: European Arms Sales to Egypt”, online at: https://timep.org/reports-briefings/timep-briefs/european-arms-sales-to-egypt/

[12] Sunniva Rose, 2022, “Lebanon: toothless watchdog ‘unable to properly monitor election”, The National News, online at: https://www.thenationalnews.com/mena/lebanon/2022/01/28/lebanon-toothless-watchdog-unable-to-properly-monitor-election/