EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

Lebanon’s political elite have historically seen local governance in the country as a threat to their dominion. Parliament’s decision in April to postpone, yet again, municipal elections until 2024 should be seen in this light. While many politicians claim the move was necessary due to a ‘lack of funding’, this is simply a convenient cover. Faced with a population battered and enraged by the country’s economic devolution since 2019, the postponement allows Lebanon’s established political parties to avoid any shake-ups in local power structures that might otherwise result.

As the national government has further fallen into dysfunction during the past four years, local municipalities have had to rapidly develop local solutions to meet the needs of their communities. Development agencies have also expanded their scope of work directly with municipalities, creating more funding opportunities for development projects traditionally managed by the national government.

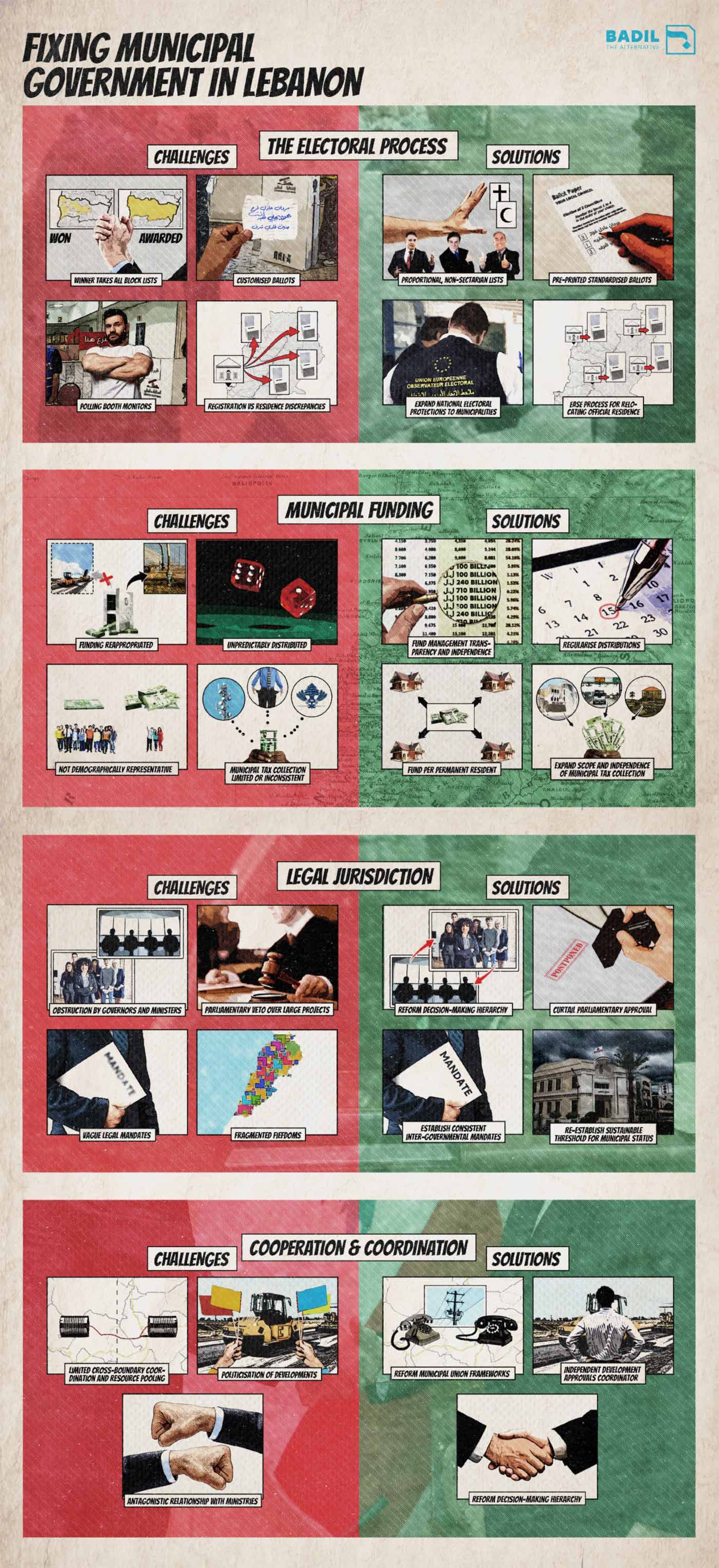

Most municipal financing comes from the national government and is often delayed. Municipal elections, legally mandated to be held every six years, have received far less scrutiny than recent rounds of national elections. They have thus been left out of partial yet important reforms to improve electoral integrity. Voters at municipal elections are often unable to vote anonymously, while also facing strong social and financial pressures from political party affiliates.

Municipal governance also remains strongly influenced by demographic patterns tying voters to their inherited town of registration, rather than where they live today. Not only does this distort demographic and funding data, it creates an accountability disconnect between voters and their local representative.

Municipalities have the potential to be important mechanisms through which to empower the popular will and generate wider political accountability. Steps to allow them to become this a potential locus for change include making municipal elections subject to the 2017 amendments to the electoral law. Among other things, this would mandate pre-printed ballots and oversight by the Supervisory Commission for Elections. Voter registration laws must also be updated to remove the unnecessary bureaucratic hurdles that prevent most Lebanese citizens from voting where they actually live.

To improve municipalities’ budget planning, the Independent Municipal Fund must be restructured to regularize payments to municipalities, redesign the allocation formula to accurately reflect municipalities’ demographics, financial needs and resource capacities.

The encroachment of other levels of government on municipal decision making must also be curtailed. Among the key areas where reforms are needed are the ability of higher levels of government to block implementation of municipal decisions, and the requirement for parliamentary approval for large- budget development projects.

LOCAL POWER’S LEVERAGE AND LIMITS

Municipal governance is supposed to be where the rubber hits the road in terms of service delivery in Lebanon, and it is the most easily accessible form of government for members of the general public. Municipalities are the final level in Lebanon’s governance hierarchy – under the national government the country is divided into eight governorates (muhafazat), which are subdivided into 26 districts (qada), below which there are currently more than 1,000 municipalities (baladiyyat).

Municipalities are led by locally elected councils that, on paper at least, exercise wide ranging power over essential service provision within their boundaries, though under varying degrees of supervision from their respective district and governorate heads, and ultimately the Minister of Interior and Municipalities. Under municipal jurisdiction are policy items such as land zoning, road construction and maintenance, waste management, electricity supply, local development projects, health infrastructure, water and sanitation, local transportation, and public spaces such as gardens. Municipalities have the power to generate revenues locally, through fees and charges, and to set their own budgets, thought their primary source of funding is the national government.1 Being directly elected by members of their local communities, they also are, theoretically, more closely accountable to their constituents than other levels of governance.

Municipalities’ potential to act with a degree of independence from the central government has, however, led many national politicians to regard them as rivals for power. 2 Lebanon’s current Municipal Act was passed in 1977 during a relative lull in what would go on to become a 15-year civil war (running from 1975-1990). The resumption of the war effectively postponed implementation of the act until the 1990s, when various central government politicians strongly resisted holding municipal councils elections under the new law. In 1998, the first post-war municipal ballot was held and was staged every six years since (2004, 2010, 2016) until last year, when the Parliament postponed the 2022 vote. Much like parliamentary elections, municipal voting has been rife with irregularities, disadvantaging independent, non- establishment representatives attempting to succeed traditional incumbents.3

The laws governing municipal elections exempted them from the reforms that were introduced to the parliamentary elections in 2017. This meant municipal elections have escaped provisions requiring a pre-printed ballot and a central electoral inspection bureau to oversee voting. Both those provisions put some limit on the predatory behaviour of establishment political party monitors commonly seen in Lebanon. As discussed below, distribution of custom ballot papers to different areas allows these monitors to know who voted for who, and without an inspection bureau there are no controls on electoral campaign spending or behaviour at polling booths.4

At a structural level, the municipal elections follow a bloc vote majoritarian system rather than the proportional system in effect for the parliamentary elections. Bloc voting for a single list of candidates creates a winner-take-all outcome, where the list of candidates that receives the most votes wins all the council seats in any given municipality. A popular list, party or candidate can thus win significant votes but still not get any representation on the council.5

Box I: Multiplying Municipalities

In the early days of the Lebanese state, communities across the country used the creation of new municipalities to assert the political will of their areas and push back against perceived central government encroachment. This led the number of municipalities to balloon from 120 in the decade prior to independence in 1943, to 400 by 1958.6 The relatively trivial legal requirements for creating a new municipality helped to facilitate this expansion in local government bodies: Until 1997, new municipalities could be formed by meeting a threshold of 300 registered voters with selfgenerated revenues above 10,000 Lebanese lira.7

This criterion was replaced in 1997 when an amendment to the Municipal Act left the right to merge or divide municipalities up the Minister of Interior and Municipalities. This shift gave the central government a means to dilute the power of any given local government body through subdividing it, and Lebanon has seen a mushrooming of municipalities since. Between 1998 and 2019, various interior in that period created at least 350 new municipalities.8 As of 2020, Lebanon with its 4 million voters had 1,108 municipalities.9

Sectarian interests often drive the splitting of municipalities. In 2022 several members of parliament discussed splitting Beirut into two municipalities, East and West. The division corresponded with longstanding demographic and sectarian divisions in central Beirut and the lines along which the city had been split during the civil war. The reminder of this level of division brought strong public opposition to the proposal and it was dropped. Had it been successful however, it would have further consolidated the demographic make-up of each municipality to be more exclusively Christian and Muslim.10, 11, 12

Similar to the way the political elite have fragmented and co-opted labour unions in Lebanon13, the potential for municipal fragmentation has allowed Lebanon’s political elite to channel their influence through local supporters willing to split off from existing municipalities. Smaller municipalities are weaker, have less financial capacity and less power to rally and represent large community groups. The Lebanese Association for Democratic Elections estimates that 90 percent of municipalities are financially unviable.14 This makes it easier for the central government to use its funding via the Independent Municipal Fund (discussed below) to leash municipal decision making. Beirut, for example, is not a fully financially independent municipality, despite its size and population, given the Independent Municipal Fund’s discretion over the city’s financing. This severely limits the Beirut municipality’s autonomy in relation to the national government.

Over the same period that the number of individual municipalities has grown, so has the number of municipal unions, which require a cabinet decree to be formed or dissolved. These bodies, also referred to as municipal federations, allow municipalities to pool resources and coordinate in public service delivery. The number of municipal unions has expanded from 13 in 1998 to 57 in 2017. Roughly 75 percent of municipalities are members of a union, with unions displaying widely variable approaches to service provision and public transparency.15