EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

The explosion that ripped through the heart of Beirut in early August took with it more than lives, dreams, and property. This calamity, caused by gross state negligence, also destroyed any remaining hope that Lebanon has a future without fundamentally reshaping its current institutions.

As the nation’s capital recovers, an opportunity presents itself to imagine and construct a fairer and more resilient system—not least in the financial sector, which lies at the heart of the current crisis. With their life savings in tatters, the Lebanese people need alternative options for storing value and running Lebanon’s finances.

Although the battle to preserve the wealth of small and medium depositors has not started well, a brighter and more equitable future for Lebanese banking could be around the corner. With enough economic vision, Lebanon’s financial meltdown may have created a critical mass of angry depositors, which can forcefully advocate for an alternative model for saving and lending. Financial cooperatives, coexisting alongside a reformed commercial banking sector, may be exactly what they are looking for.

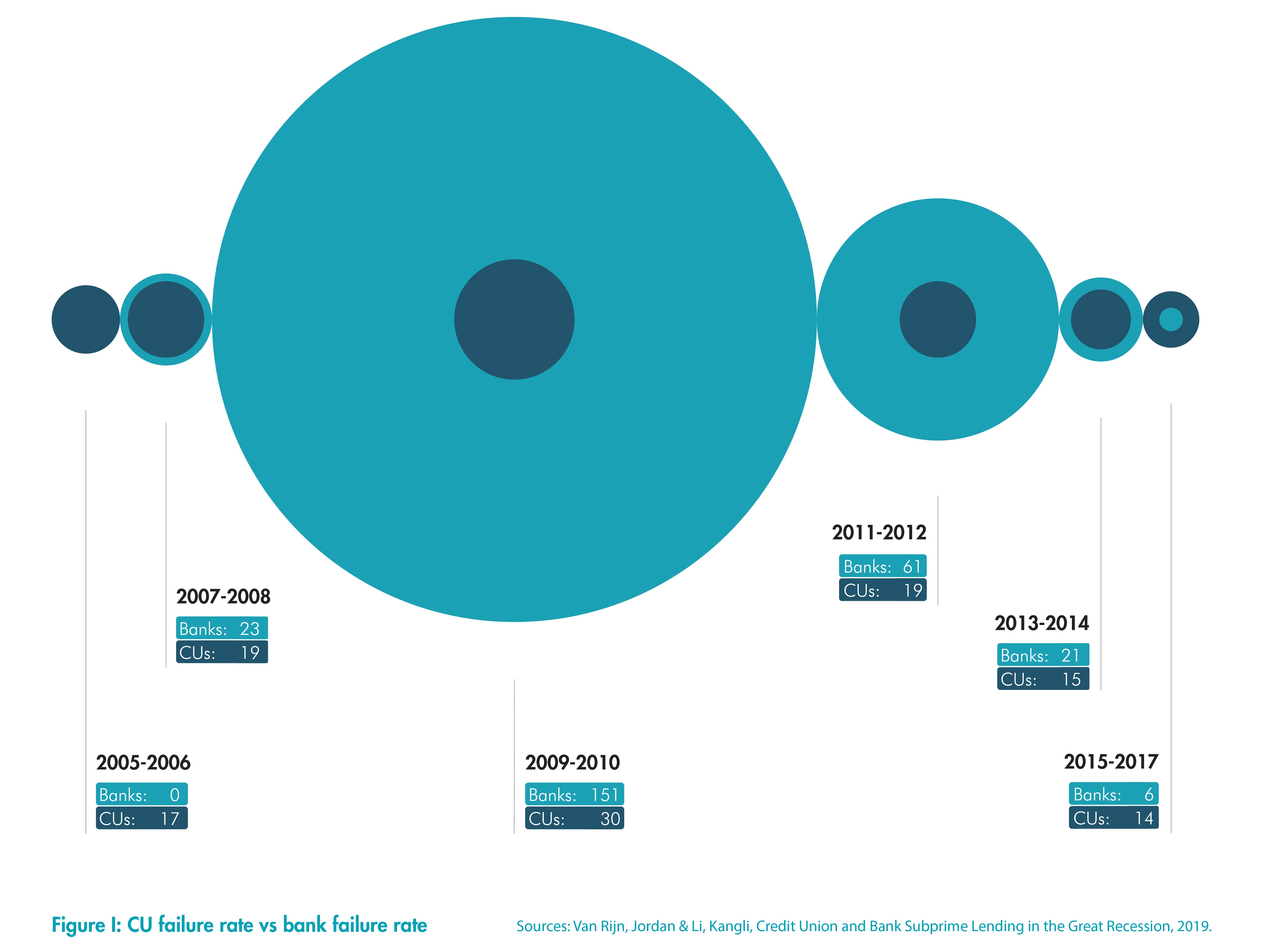

Credit unions and other types of financial cooperatives have the power to diversify Lebanon’s homogeneous banking sector. This would serve Lebanon well in the rocky years ahead; research shows that when banks do poorly, credit unions often do much better.

Credit unions are also better than banks at providing marginalised groups with financial services. Lebanon suffers from poor financial inclusion, with a mere 45 percent of adults in Lebanon owning bank accounts. However, despite the obvious need, credit unions have never existed in Lebanon.

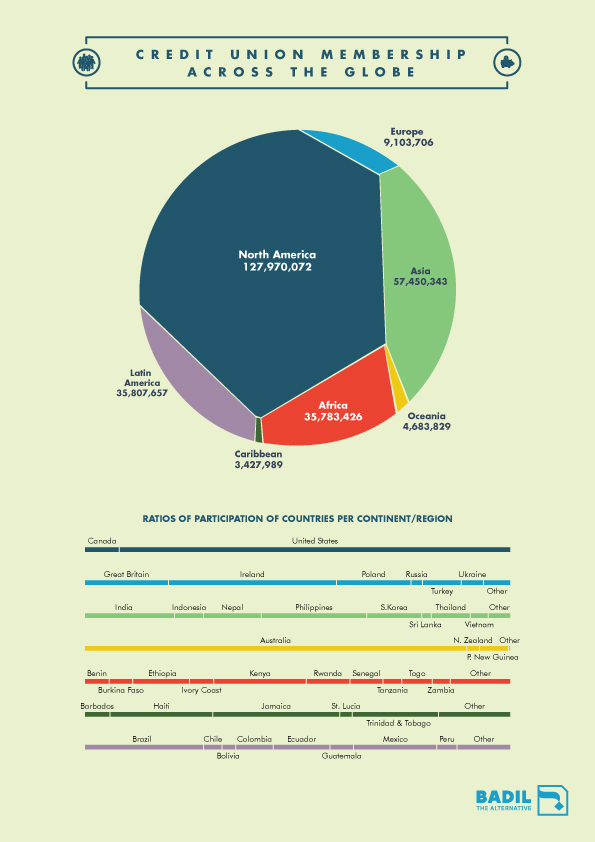

Due to calculated disinterest, state and political elites never allowed financial cooperatives to appear in Lebanon’s economic ecosystem. This retrograde attitude defies trends in other corners of the world, from the United States to Senegal, where cooperative banks have brought much-needed accountability, democratic principles, and resilience to financial shocks. Instead, faced with a crumbling national currency, the Lebanese are desperately searching for new stores of value—but they are met by obstacles at every turn.

Investing in physical assets can be unsustainable; vulnerable to theft and unexpected market collapse, the trend for luxury cars and real estate is likely to be short-lived. Optimists argue that the increased trade in cryptocurrencies such as Bitcoin, for example, could herald an equitable exit from Lebanon’s nightmarish currency.

But cryptocurrency is only an option for a group of Lebanese who are practically on the verge of extinction: those fortunate enough to have expendable income in foreign currency. Without extensive reform to the Electronic Money Transfer (EMT) sector, cryptocurrency cannot hope to offer the Lebanese the kind of respite it did during other financial meltdowns, such as in Venezuela.

Only breaking with tradition will allow the country to end the current economic crisis. It is now up to depositors to campaign for a more equitable path for finance in Lebanon.

INTRODUCTION

For nearly all of the 20th century, Beirut served as a bank to the region. When the French entered the city in 1919, they chose to print the new local paper currency—the Syrian lira—from an office in Beirut’s Ain el-Mraisseh district.1 After independence in 1943, bankers cemented the city’s legacy as a free-wheeling, laissez-faire business hub aiming to attract investment from the powerful players du jour. This legacy’s keystone was the infamous 1956 Banking Secrecy Law, which allowed the sector to balloon throughout the 1960s. Today, the banking sector contains around 60 commercial banks, making Lebanon one of the world’s most densely banked countries per capita.2

In late 2019, the banking sector imploded [See: Extend and Pretend, 2019]. The ensuing financial chaos had a disproportionately harsh impact on small and medium depositors in Lebanese banks. These accountholders suffered due to the unfair application of informal capital controls from October 2019 onwards, while wealthier bank customers likely whisked away their money to offshore accounts. Money that remained inside Lebanon has been converted to Lebanese lira at an unfavourable rate, slashing lifetime savings across the country. These catastrophic developments have left Lebanon’s dwindling middle class with a conundrum: where to store their money.

Many have already decided that stashing cash at home is safer than keeping it in banks, causing the sale of “cash-in-safe” insurance policies to sky-rocket.3 However, keeping cash under the mattress is neither sustainable nor safe. More thefts and robberies were recorded in the first half of 2020 than in the whole of 2019, according to Lebanon’s Internal Security Forces.4 Some Lebanese are already looking elsewhere for new stores of value, such as cryptocurrency and physical assets. But these forms of investment have their own drawbacks. Moreover, they are more accessible to the lucky few with access to foreign currency that arrived in Lebanon after October 2019, known locally as “fresh” US dollars. In reality, they are exclusive solutions to a problem which affects all depositors, particularly small and medium depositors.

Before Lebanon’s financial crash, bankers lauded the country’s plethora of banks as giving depositors greater choice and better services for their savings. Despite their claims of variety, there was always something conspicuously lacking in Lebanon’s financial landscape: financial cooperatives, such as credit unions. The financial crash provides an unparalleled opportunity for these much-needed member-owned saving and lending systems to flourish. But how could these member-owned institutions help the Lebanese, and why have they never existed?

ANALYSIS

CREDIT TO THE UNION

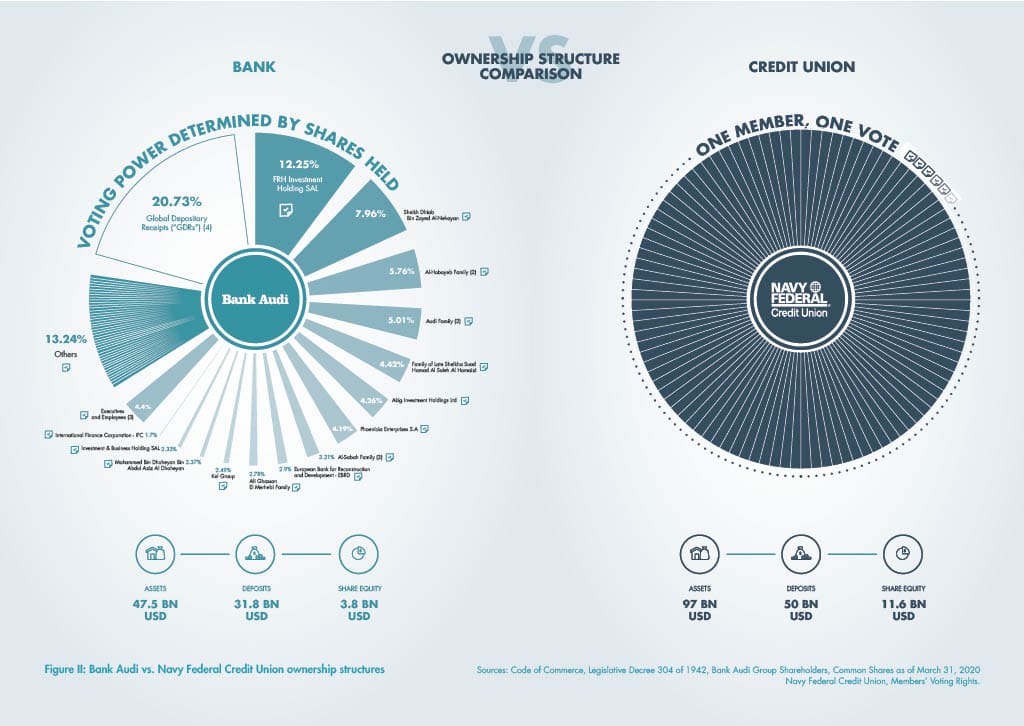

Plenty of different organisations can be grouped under the umbrella term “financial cooperatives,” including credit unions, building societies, cooperative banks, and savings and credit cooperatives. Like banks, financial cooperatives provide financial services— such as savings accounts and loans—for depositors. Yet, unlike banks, financial cooperatives are owned by the same people they intend to serve. For this reason, financial cooperatives place a strong emphasis on social solidarity, referring to their depositors as members, not customers.5

Guided by the principle of “one member, one vote,” financial cooperatives offer their members greater control over their money than traditional banks. Every member has an equal vote in all decisions affecting the cooperative, making the cooperative directly answerable to its members rather than simply profit-driven executives or shareholders.6 Financial cooperatives promote financial inclusion, typically boasting better customer service and lower fees than commercial banks. Importantly, however, financial cooperatives do not seek to replace commercial banks—historically, they have offered an alternative for depositors (especially in rural communities) who have trouble accessing credit through the commercial banking system [See Box I: A Short History of Financial Cooperatives]. Indeed, many economists argue that they complement banks, helping diversify the financial sector and providing stability in times of recession.7

BOX I: A Short History of Financial Cooperatives

The first cooperatives banks were recorded in nineteenth century Germany.8 After initially reacting with suspicion, German federal authorities eventually created legal structures based on those used for already functioning agriculture and retail cooperatives. This financial cooperative model was easily imitated and spread elsewhere in Europe.9 But similar concepts existed elsewhere, independent of the German model. From as early as the 14th century, the Japanese Tanomoshi-ko – literally meaning trustworthy community—provided financing to the poor without collateral or interest payments.10 In Arabic-speaking countries, a similar system of rotation savings known as a jama’ieh has long provided a basic alternative to commercial lending. However, these small-scale associations never received the state backing necessary to grow bigger than several dozen members. Today credit unions serve poorer segments of society across the world, often acting as an entry point into the formal financial system.11

Financial cooperatives do suffer certain drawbacks compared with traditional banks. Credit unions offer fewer financial services or “products,” meaning that members have fewer saving and borrowing options than bank customers. Since credit unions are generally smaller scale than banks, they also have fewer physical branches, making them less convenient for in-person visits. Smaller credit unions are often less able to invest in technology, for instance, meaning that their online and mobile services are sometimes under-developed.

Cooperative business models are remarkably resilient in times of crisis—such as the ones Lebanon is currently experiencing. Banking is no exception. Forms of financial cooperatives have proven that they can withstand banking crises, economic recessions and conflict better than the traditional commercial banks.12 This is largely thanks to the risk-averse nature of financial cooperatives; unlike banks, credit unions do not aim to maximise their profits. Instead, to keep their non-profit status, they are legally obliged to re-invest any surplus funds into the cooperative or distribute it among members.13 Neither are cooperative decision makers rewarded for risky behaviour like their banking counterparts. Credit union CEOs receive two-and-a- half times less performance-based compensation than their counterparts at banks. This impacts board room representation; 52% of credit union CEOs are female, compared to only 4% of commercial bank CEOs.14