Built to flood or not built at all

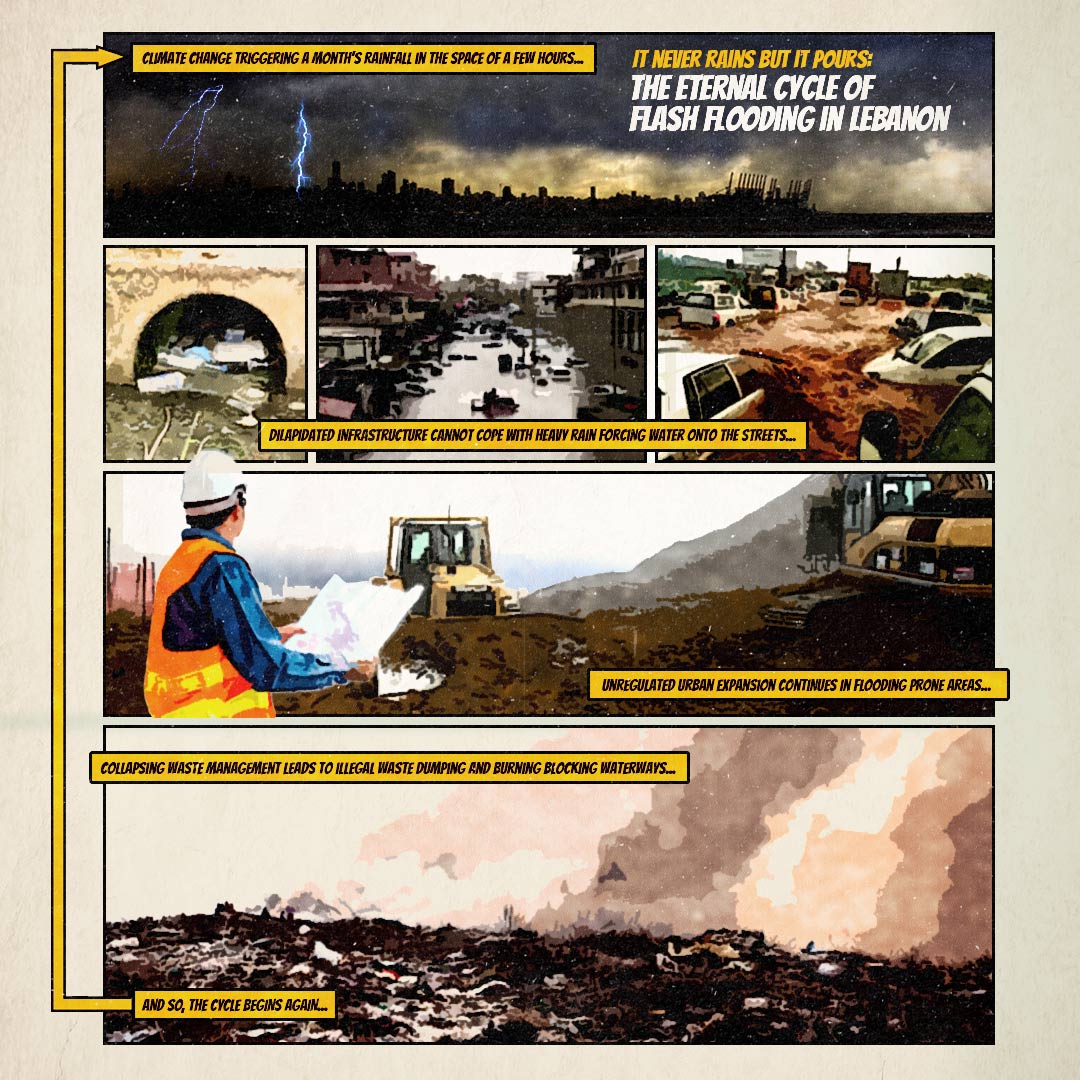

Whether heavy rains lead to flash floods or not depends in large part on topography. In Lebanon, the government’s failure to build proper urban infrastructure is clearly exposed when the winter storms descend. This negligence includes decades of overseeing the construction of roads and bridges over waterways, the unregulated building on riverbanks and flood-prone areas, and failing to upkeep drainage systems that do exist, according to experts who spoke with The Alternative. This is visible in the rapid and often chaotic urban expansion in and around Lebanon’s capital. A prime example is the growth of the Bourj Hammoud neighbourhood, directly on the banks of the Beirut River, according to Savelli. Of the neighbourhood’s gullies and drains, 83% are damaged or non-functional, in turn contributing to localised flooding during heavy rainfall.

Flash flooding is also common in the coastal regions of the Kersewan-Jbeil Governate, especially in the cities of, and highways connecting Jbeil, Jounieh, and Zouk Mosbeh. This is no coincidence. These coastal regions are some of the most heavily urbanised in the country, explained Mario Al Sayah, previously a researcher at the Lebanese National Centre for Scientific Research (NCRS) who now works on urban adaptation to climate change.

Despite the annual recurrence of flooding in Jounieh, the Director-General of Roads and Buildings at the Ministry of Public Works, Tanios Boulos, pinned the flooding in late-November 2022 on an unprecedented amount of rainfall. The Director General went on to tell The Alternative that Jounieh’s infrastructure is usually well prepared for winter rains. The damage inflicted by flash flooding last year, and in previous years, suggests otherwise.

Infrastructure planning simply has not kept up with changes in Lebanon’s demographic makeup and the rapid urban growth in coastal areas. Between 1960 and 2021, the proportion of the country’s population residing in urban areas more than doubled, from 42% to 89%. Urban planning policy in Lebanon remains, however, remains haphazard and decades out-dated.

The most important legislation in the country on the subject is The Urban Planning Code (Law No. 63), passed in 1983. With a focus on zoning and street networks, in theory the law requires cities and towns that are the administrative centres of districts to have master plans for development, though with certain opt-out clauses for both urban and rural areas. These plans also require ministerial approval to be made legal. Implementation of the law has, however, been anaemic. Today, only 15% of the country is covered by master plans, the rest is either unplanned or subject to partial plans for specific areas. The many development plans that have not received ministerial approval are legally suspect. The Law also does not include any provisions for climate-change awareness in urban planning.

In the absence of a central ministry tasked with regulating urban development, various institutions filling this vacuum include the municipalities, the Directorate General of Urban Planning, and the Council for Development and Reconstruction (CDR). This has led to a haphazard regulation guided by differing agendas on local and national levels. A cabinet seat for a Minister of State for Planning was established in 2016, but little changed, and the seat has been vacant for the past four years.

Government coordination? Just garbage

The prevalence of illegal waste dumping in recent years, the product of Lebanon’s landfills currently functioning beyond full capacity coupled with a legislative deadlock, has led to a country-wide trash crisis. Only 20% of Lebanon’s waste was “recovered” as of 2020. The remaining 80% of “unrecovered” waste is either subject to open burning or illegal dumping, the latter of which exacerbates the likelihood of flash flooding. Blocked drainage systems and natural waterways are unable to absorb rainwater which accumulates and is subsequently diverted onto streets and into inhabited areas.

The municipalities are legislatively tasked with dealing with the “first stages” of waste management, including reducing waste production and sorting at the source, according to a 2015 waste management plan issued by the Council of Ministers. This decentralisation to the municipalities was extended by a 2018 Solid Waste Management Law. However, it is also the remit of the Ministry of Public Works to maintain infrastructure and keep drainage systems clear to ensure flooding does not occur, said Samar Khalil, an expert at the Waste Management Coalition, a collection of non-governmental organisations, experts, and activists working for sustainable waste management in Lebanon.

Such jurisdictional overlap has provided plentiful space for political blame trading. Take, for example, the caretaker minister of public works’ social media swipes in November, questioning why the municipalities and waste management companies had failed to clear waste from blocked drainage systems. The waste removal company Ramco retorted: “We wish that the minister had asked us or the Council for Development and Reconstruction or the Environment Ministry the question directly … he would have gotten the answer and solution immediately, if he actually wanted it.”

Official requests for the central government ministries to clarify their policies and responsibilities have been met with either silence or deliberate evasiveness. Member of Parliament Ibrahim Mneimneh submitted a comprehensive list of questions to the “entire Lebanese government” regarding its official policy towards the causes and impacts of flooding in Lebanon. These included inquiring as to the existence of a general plan at the Ministry of Public Works to reduce recurrent flooding, and if any surveys were being undertaken to better understand the phenomenon in flood-prone areas. Mneimneh told The Alternative that he received no response from any of the ministers he had directly referenced. While the CDR responded, it did not address any of Mneimneh’s questions. Instead, the CDR provided a “list of the (waste management) stations [and] whether they were functioning or not.”

Searching for higher ground

Tackling the systemic problems that trigger flash flooding every year – the collapsing waste management system, unsustainable urban expansion and neglected infrastructure – remains unlikely as long as Lebanon’s political establishment claims confusion over jurisdictional remit.

A starting point would be finding “proper organisation between different institutes, [and] major stakeholders that are playing roles, especially the municipalities”, explained Chadi Abdallah, associate researcher at the Lebanese National Council for Scientific Research, in an interview with The Alternative. The establishment of a parliamentary sub-committee focused on unpicking questions of jurisdictional remit regarding flooding would prove essential in facilitating this. Similarly, resurrecting the National Committee for the Management of Solid Waste, established by Law 80 in 2018 but currently inactive, according to Khalil, would provide legislative oversight on the issue of waste management.

The ongoing financial crisis that has seen many Lebanese intellectuals leave the country. Despite this, the government still retains frameworks to integrate scientific opinion into policy making if it chose to do so. The most notable of which is the National Centre for Remote Sensing, established in 1995 as a “support for decision making” on natural disaster risk reduction.

“The current approach is still reactive not proactive when it comes to legislation,” stated Sayah. The World Bank provided a $200 million loan to Lebanon for The Roads and Employment Project in 2017. The Project, implemented by the CDR, involves the “repair of drainage systems and road retaining walls”, according to Transportation Engineer and Project Director at the CDR, Elias Helou. A status report noted that the project had resulted in 121 km of road receiving “improved drainage systems” as of January 2023.

All the flooding defence measures outlined in the project aims are, however, ‘gray’ measures. This academic term refers to flooding defence solutions based in further construction and engineering projects. While such flooding defence projects provide help reduce the damage inflicted by heavy rains, their impact is limited if they are not integrated within a larger flooding prevention framework. Sayah recommends the multiple benefits of incorporating ‘nature-based solutions’ into flood response and prevention planning in Lebanon. Crucially, they offer a more cost effective and resilient approach to flooding than ‘gray’ solutions alone, according to research by The World Bank.

In Lebanon, this would encompass projects aiming to sustainably manage and restore ecosystems, which can be used in conjunction with ‘gray’ solutions. Sayah referenced, for example, the possibilities of floodable parks in Lebanon. These would provide a vegetation-based filtration system for stormwater while, when it is not raining, providing rare public space for Lebanese.

Lebanon’s flash flooding will only increase as climate change heralds a fatal combination of prolonged dry periods and outbursts of intense rain. As long as the necessary reforms are neglected by the political establishment, an already fragile country will have to weather more devastating flash floods in the winters ahead.