Slipping standards

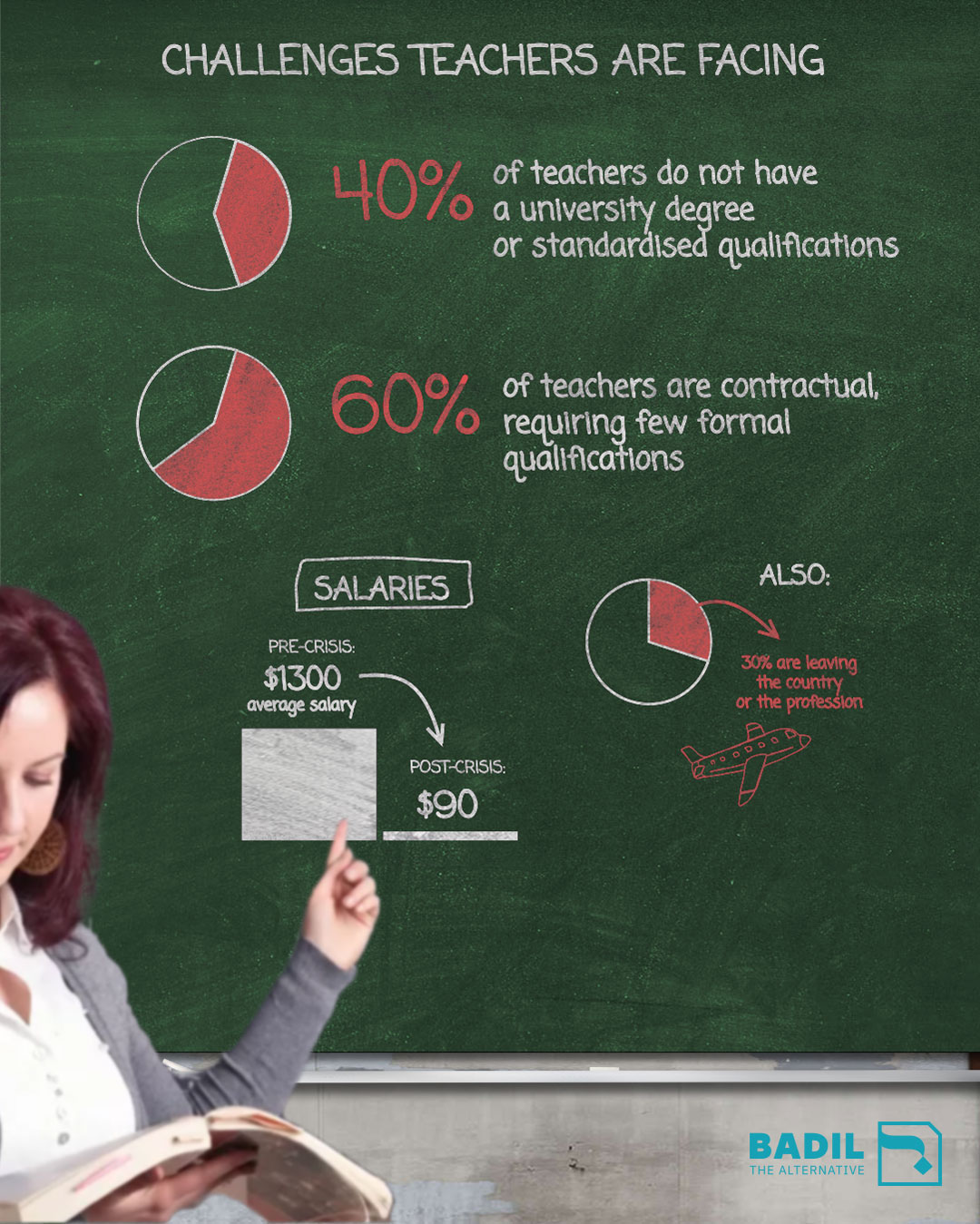

Lebanon’s relative dearth of skilled, well-trained, highly motivated teachers is, in part, another outcome of the country’s post-Taif neoliberalisation. Before the civil war, Lebanon’s teachers were trained by Dar al-Mualemeen – a network of teacher-training colleges dating back to 1931. The colleges were gradually dismantled through reforms implemented by the MEHE’s Centre for Educational Research and Development (CERD)[39] from the 1970s, as teacher contracting became more prevalent.

As teacher training became less rigorous and consistent, and the number of contractual teachers grew, the bloated education workforce became a significant drain on the government’s education budget. Before 2019, it is true that many teachers – most particularly those in kindergarten and primary schools – received lower than average salaries, disincentivising skilled applicants.[40] But, at the same time, average salaries for secondary-school teachers were inflated out of proportion to the skill level of the workforce.

Corrupt hiring practices have not gone unnoticed by teaching staff, contributing to professional dissatisfaction and poor performance. The MEHE itself has acknowledged that there is significant mistrust among teachers, many of whom believe that positions are not secured on merit but instead on politics.[41] The MEHE has also acknowledged that the existing recruitment approach “results in difficulties in the recruitment of teachers with the appropriate expertise, language [skills], and/or content [knowledge].”[42] Now, both teacher recruitment and retention are urgent issues.

Governance limbo

The Lebanese government’s 2021–2025 General Education Plan contains a detailed description of the challenges that faced the education system pre-2019 and lays out strategies to overcome these challenges and improve the quality, consistency, and sustainability of the education system.

This is no easy feat. The plan identifies four key hurdles to addressing the current crisis in the sector: “The capacity of the educational administration at all levels; the available funding; the coordination among the different actors; and the uncertainties that are inherent to the present context.”[43]

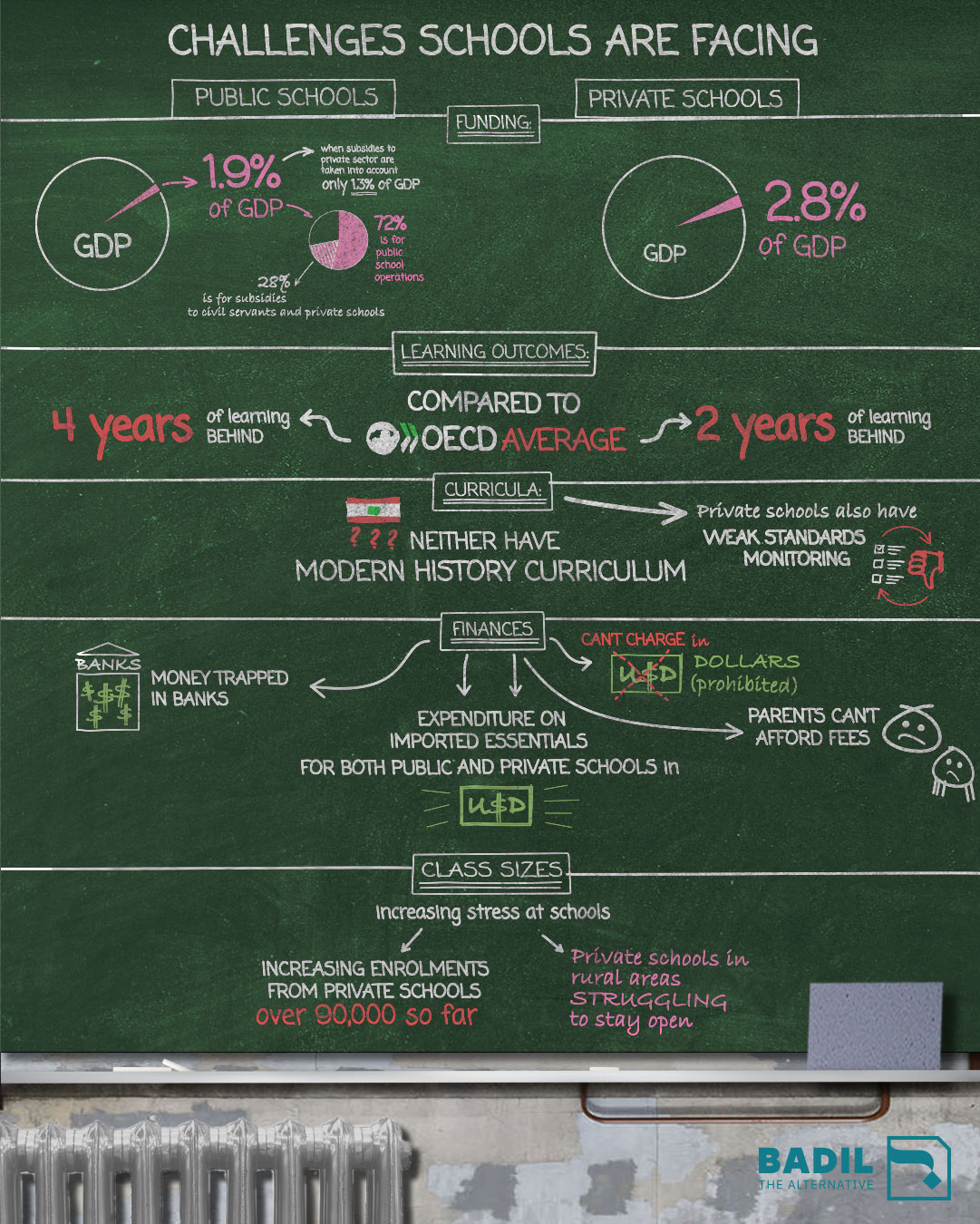

Although the plan goes on to suggest methods of remediation, that second hurdle, funding, remains a gaping hole in the document. Most sections related to budgeting are left blank, reflecting the binding of the MEHE’s fate to that of the broader economic and governance crisis facing the country. Estimates of pre-crisis funding for the plan show that US$300 million per year was needed to achieve its targets.

Under the MEHE’s pre-crisis budget, only US$200 million was available.[44]

In terms of government financing then, this five-year plan remains simply words on paper. It seems unlikely that the state will find a way to resource all, or even some, of its suggested initiatives. What, then, of other potential funding streams?

During the 2021–2022 school year, the World Bank supported the MEHE with a monthly US$90 incentive for teachers to return to school, which was designed to help cover their transport and other logistical costs.[45] This funding did not, however, extend to the 2022–2023 school year. As yet, there are few indications of how the donor community intends to respond to the collapsing education system going forward.

The growing lack of trust in the government’s intention or ability to resolve the economic crisis – in addition to calls to no longer channel aid through the government following the Beirut Port explosion – have made donors of all stripes more circumspect in their support.

Recommendations

The Lebanese government should increase national expenditure on education to 4–6% of GDP, in line with international benchmarks. The foundational nature of education for social, economic, health, and other outcomes requires that Lebanon make rescuing and reforming the education sector a high priority. Government expenditure on education is considered among the best fiscal stimuli to support a recovery from shocks like COVID-19, as it aims at limiting lost opportunities for long-term economic growth.[46]

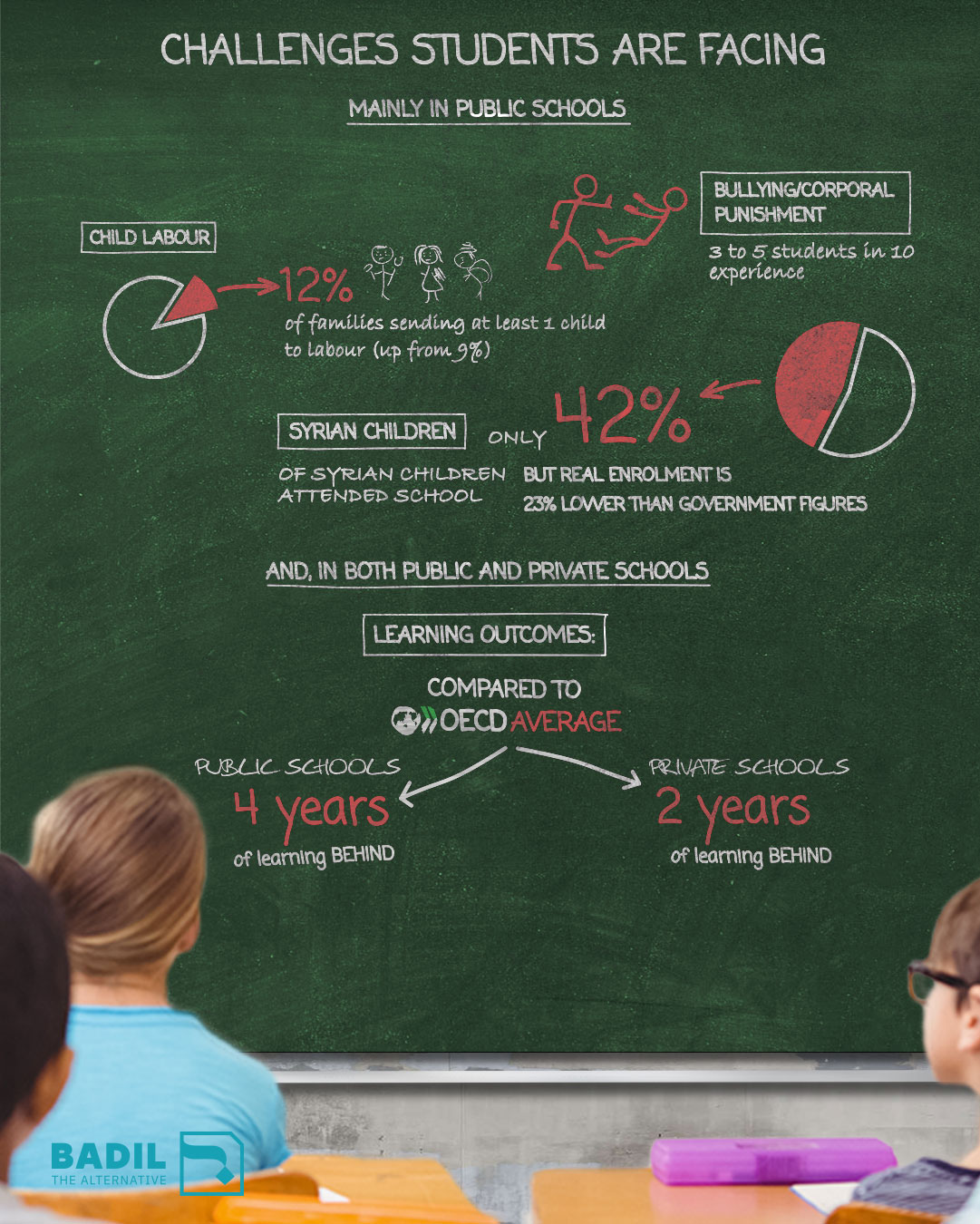

The current disruption to the education system has exposed the vulnerabilities inherent in relying on private education and chronically underfunding public education. Responses to this crisis should be designed to achieve the long-term goal of strengthening public education as a cornerstone of civil life in Lebanon, with curricula that encourage social cohesion, critical thinking, and human development.

Given the urgent challenges facing the sector and in the absence of government action, nongovernmental actors and the international community must now consider reorienting their education responses from development initiatives to emergency programming.

Emergency interventions

International donors must find ways to continue support for teacher-incentive payments without reducing pressure on the Lebanese government to quickly and comprehensively address the ongoing financial crisis. The donor community must negotiate a funding position that does not allow the Lebanese government to continue abrogating its responsibility. Any funding needs to be accompanied by strict, independent monitoring protocols to ensure payments are efficiently and equitably delivered to teachers across the school system, in US dollars.

Emergency cash-transfer programmes should be expanded to include parents with children enrolled at primary schools, to relieve economic pressures that might compel them to pull children from school. These transfers should also include strict monitoring protocols to ensure attendance at schools and be sufficient to cover transport, learning materials, and food. Monitoring protocols involved with these cash transfers should include expanded powers for social workers and health advisors at schools to monitor child-protection concerns.

BDL must direct commercial banks to distribute funds from donors and those held in school savings accounts in the currency in which they were deposited, or risk prosecution. BDL must also direct banks to grant public schools access to their accounts. Banks failing to do so should be held liable for blocking emergency aid and for violations under the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child.

The donor community must consider conflict sensitive and transparent modalities to support private schools to stay open. Given the current crisis, particularly in public schools, and the fact that most students are still outside the public system, private schools must stay open to maintain access to education. Means-tested cash-transfer programmes to cover essential costs, such as fuel, for families with children attending private schools could avoid funding private entities directly and should be expanded. Private schools in areas where there are no nearby public schools should be prioritised.

The international community and Lebanese government must prepare contingency plans should a significant number of private schools close and public schools be faced with an unmanageable number of transfer students. This planning should be oriented to a longer-term view of merging more private schools – particularly nondenominational schools and independent free-private schools – into the public system.

Lebanon’s national child-protection and referral systems must be supported to rapidly scale-up labour inspections at schools and expand social-protection programmes. The MEHE and its child-protection and education partners should simultaneously enhance the collection and exchange of data on out-of-school children and other gaps in the sector, to adequately inform current and future plans and interventions.

Medium-to-long-term interventions

Addressing Lebanon’s distorted teacher-student ratio should come as a part of overhauling school governance and management. Teaching modalities that necessitate overstaffing at small regional schools should be reformed to enable teachers to teach multiple classes and subjects. Teachers should be trained and certified as teachers via a formal accreditation process. The overhaul of teaching staff will necessitate the dismissal of many contractual teachers, while those who remain will have to undergo training and recertification. Teacher pay scales should also be revised to better incentivise balanced distribution of high-quality teachers across kindergarten, primary, and secondary schools.

The MEHE must develop an education inspection framework with graded criteria to monitor private and public schools. This will help to monitor schools’ curricula and teaching quality and pave the way for school improvement plans, with the prospect of delivering greater equity of education across the country. This inspection of schools should be carried out by a body independent from the MEHE. Teachers’ working hours and students’ outcomes should also be monitored as a part of standard assessments across all schools.

The government’s subsidies to free-private schools must be redirected to parents who qualify for assistance based on comprehensive means testing. This should involve vouchers to poorer households to incentivise access to public or private schools. Further, all private schools that wish to continue operating must pass rigorous performance evaluations and financial auditing, and implement a quota of enrolment slots that are accessible to economically vulnerable households.

Lebanon must update its curricula to meet the needs of the modern workforce and to standardise and strengthen the monitoring of teacher and student performance. Monitoring school performance requires a standard measure against which student performance can be tracked. This means school teaching outcomes and curricula must be standardised, which also would serve as a further step in ensuring children receive equal-quality education. Gaps in curricula – for instance, those in the history curriculum – must be filled. This process can be seen and implemented as an opportunity for national dialogue and reconciliation.

Editor’s note: The editors and author would like to thank Maysa Mourad for her contributions to this policy paper.

[1] Husein Abdul-Hamid and Mohamed Yassine, Political Economy of Education in Lebanon: Research for Results Program (World Bank, 2020).

[2] UNICEF (2020) “Violent Beginnings: Children Growing Up In Lebanon’s Crisis, Unicef, December 2021, online at https://www.unicef.org/lebanon/reports/violent-beginnings

[3]“Learning losses from COVID-19 could cost this generation of students close to $17 trillion in lifetime earnings,” UNICEF, December 6, 2021: https://www.unicef.org/press-releases/learning-losses-covid-19-could-cost-generation-students-close-17-trillion-lifetime.

[4] Article 10 of the 1926 Lebanese Constitution holds that: “Education shall be free insofar as it is not contrary to public order and morals and does not affect the dignity of any of the religions or sects. There shall be no violation of the right of religious communities to have their own schools provided they follow the general rules issued by the state regulating public instruction.”

[5] Abdul-Hamid and Yassine, Political Economy of Education in Lebanon (World Bank, 2020).

[6] See the preamble of Lebanon’s constitutional law of September 21, 1990. Paragraph G holds that: “The even development among regions of educational, social, and economic levels shall be a basic pillar of the unity of the state and the stability of the system.” Paragraph I stipulates: “There shall be no segregation of the people based on any type of belonging.”

[7] Habib Battah, “Not your average citizen: Rafik Hariri’s neoliberal Lebanon,” Beirut Report, November 20, 2017: https://www.beirutreport.com/2017/11/not-your-average-citizen-rafik-hariris-neoliberal-lebanon.html.

[8] “Foundations for Building Forward Better: An Education Reform Path for Lebanon,” World Bank, June 14, 2021.

[9] Julia Mahfouz, “Neoliberalism – The Straw That Broke the Back of Lebanon’s Education System,” in Neoliberalism and Education Systems in Conflict: Exploring Challenges Across the Globe, edited by Khalid Arar, Deniz Örücü, and Jane Wilkinson (Routledge, 2021).

[10] Abdul-Hamid and Yassine, Political Economy of Education in Lebanon (World Bank, 2020).

[11] Ibid.

[12] Ibid.

[13] It should be noted here that at least some of the subsidies to “free-private” schools – which officially amount to around 1 million lira per student per year (equivalent to US$700, before the 2019 financial crisis) – have not been paid since 2017, according to both a source in a Christian private school syndicate and a senior government advisor.

[14] Abdul-Hamid and Yassine, Political Economy of Education in Lebanon (World Bank, 2020).

[15] Ibid.

[16] The OECD’s Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) surveys 15-year-old students to “assesses the extent to which they have acquired the key knowledge and skills essential for full participation in society.” See: “Lebanon Country Note: PISA 2018 Results,” OECD, 2019: https://www.oecd.org/pisa/publications/PISA2018_CN_LBN.pdf; Abdul-Hamid and Yassine, Political Economy of Education in Lebanon (World Bank, 2020).

[17] Abdul-Hamid and Yassine, Political Economy of Education in Lebanon (World Bank, 2020).

[18] Richard Salame, “Lebanese lira lost 82 percent of its purchasing power in two-year period, UN data shows,”

L’Orient Today, February 3, 2022: https://today.lorientlejour.com/article/1289780/lebanese-lira-lost-82-percent-of-its-purchasing-power-in-two-year-period-un-data-shows.html.

[19] Interview with senior government official who wishes to remain anonymous.

[20] “Briefing Note: Lebanon Humanitarian Impact Of Crisis On Children,” ACAPS, June 2, 2022: https://reliefweb.int/report/lebanon/acaps-briefing-note-lebanon-humanitarian-impact-crisis-children.

[21] “Lebanon’s ‘new poor’ pull children out of private school,” France 24, August 18, 2021: https://www.france24.com/en/live-news/20210831-lebanon-s-new-poor-pull-children-out-of-private-school.

[22] “Physical violence in Lebanon’s schools ‘amounts to rights abuse’: HRW,” New Arab, May 10, 2019: https://english.alaraby.co.uk/analysis/physical-violence-lebanons-schools-amounts-rights-abuse.

[23] “Bullying in Lebanon: Research Summary,” Save the Children, October 2018: https://lebanon.savethechildren.net/sites/lebanon.savethechildren.net/files/library/STC_Bullying%20in%20Lebanon_Research%20Summary_English.pdf.

[24] “Deprived of the basics, robbed of their dreams, children in Lebanon lose trust in their parents,” UNICEF, August 25, 2022: https://www.unicef.org/press-releases/deprived-basics-robbed-their-dreams-children-lebanon-lose-trust-their-parents.

[25] Andrea Lopez-Thomas, “Children’s education at risk in Lebanon due to economic crisis,” Al-Monitor, March 24, 2022:

https://www.al-monitor.com/originals/2022/03/childrens-education-risk-lebanon-due-economic-crisis.

[26] “Vulnerability Assessment of Syrian Refugees in Lebanon: Preliminary Findings,” UNHCR, September 29, 2021: https://data2.unhcr.org/en/documents/details/88960.

[27] Triangle research on child labour conducted for the ILO in 2021.

[28] “Violent beginnings: Children Growing Up in Lebanon’s Crisis”, UNICEF, December 2021: https://www.unicef.org/lebanon/reports/violent-beginnings.

[29] Ibid.

[30] Maha Shuayb, “Lebanon: ‘Ahmed Will Not Be Part of the One Percent’,” Daraj, March 18, 2021: https://daraj.com/en/68496/.

[31] “يسقط حكم الفاسد – مدارس من رمل” [Down with the rule of the corrupt – Schools of sand], Al Jadeed TV, 2020: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2bEZusgS4PM&t=66s.

[32] “Lebanon: Action Needed on Syrian Refugee Education Crisis,” HRW, March 26, 2021: https://www.hrw.org/news/2021/03/26/lebanon-action-needed-syrian-refugee-education-crisis.

[33] “Briefing Note: Lebanon Humanitarian Impact Of Crisis On Children,” ACAPS, June 2, 2022: https://reliefweb.int/report/lebanon/acaps-briefing-note-lebanon-humanitarian-impact-crisis-children.

[34] “Pupil-Teacher Ratio, Secondary – Jordan, Lebanon, Turkey,” World Bank, February 2020: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SE.SEC.ENRL.TC.ZS?locations=LB-TR.

[35] A. Al-Amin, “The policy of appointing contractors to the public service in Lebanon: The example of official teachers,” Lebanese National Defence, Issue 82 (October 2012): https://tinyurl.com/2p9cuffz.

[36] Abdul-Hamid and Yassine, Political Economy of Education in Lebanon (World Bank, 2020); Interview with senior government official who wishes to remain anonymous.

[37] “Lebanon Five-Year General Education Plan 2021–2025,” Lebanese Ministry of Education and Higher Education, 2020; Interview with senior government advisor who wishes to remain anonymous.

[38] Abdul-Hamid and Yassine, Political Economy of Education in Lebanon (World Bank, 2020).

[39] The CERD – a public institution with financial and administrative autonomy, under the custodianship of the Minister of Education – was established in 1971. It acts as the primary planning and review body responsible for assessing and addressing issues of quality, resourcing and standards within the education system, among other functions.

[40] “Lebanon – Education Public Expenditure Review 2017,” World Bank, June 22, 2018: https://documents.worldbank.org/en/publication/documents-reports/documentdetail/513651529680033141/lebanon-education-public-expenditure-review-2017.

[41] “Lebanon Five-Year General Education Plan 2021–2025,” Lebanese Ministry of Education and Higher Education, 2020.

[42] Ibid.; “Lebanon – Education Public Expenditure Review 2017,” World Bank, June 22, 2018: https://documents.worldbank.org/en/publication/documents-reports/documentdetail/513651529680033141/lebanon-education-public-expenditure-review-2017.

[43] “Lebanon Five-Year General Education Plan 2021–2025,” Lebanese Ministry of Education and Higher Education,

[44] Interview with senior government official who wishes to remain anonymous.

[45] “World Bank Statement on Incentive Program for Lebanon’s Public-School Teachers for the Academic Year 2021–2022,” World Bank, December 23, 2021: https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/statement/2021/12/23/world-bank-statement-on-incentive-program-for-lebanon-s-public-school-teachers-for-the-academic-year-2021-2022.

[46] “Foundations for Building Forward Better: An Education Reform Path for Lebanon,” World Bank, June 14, 2021.