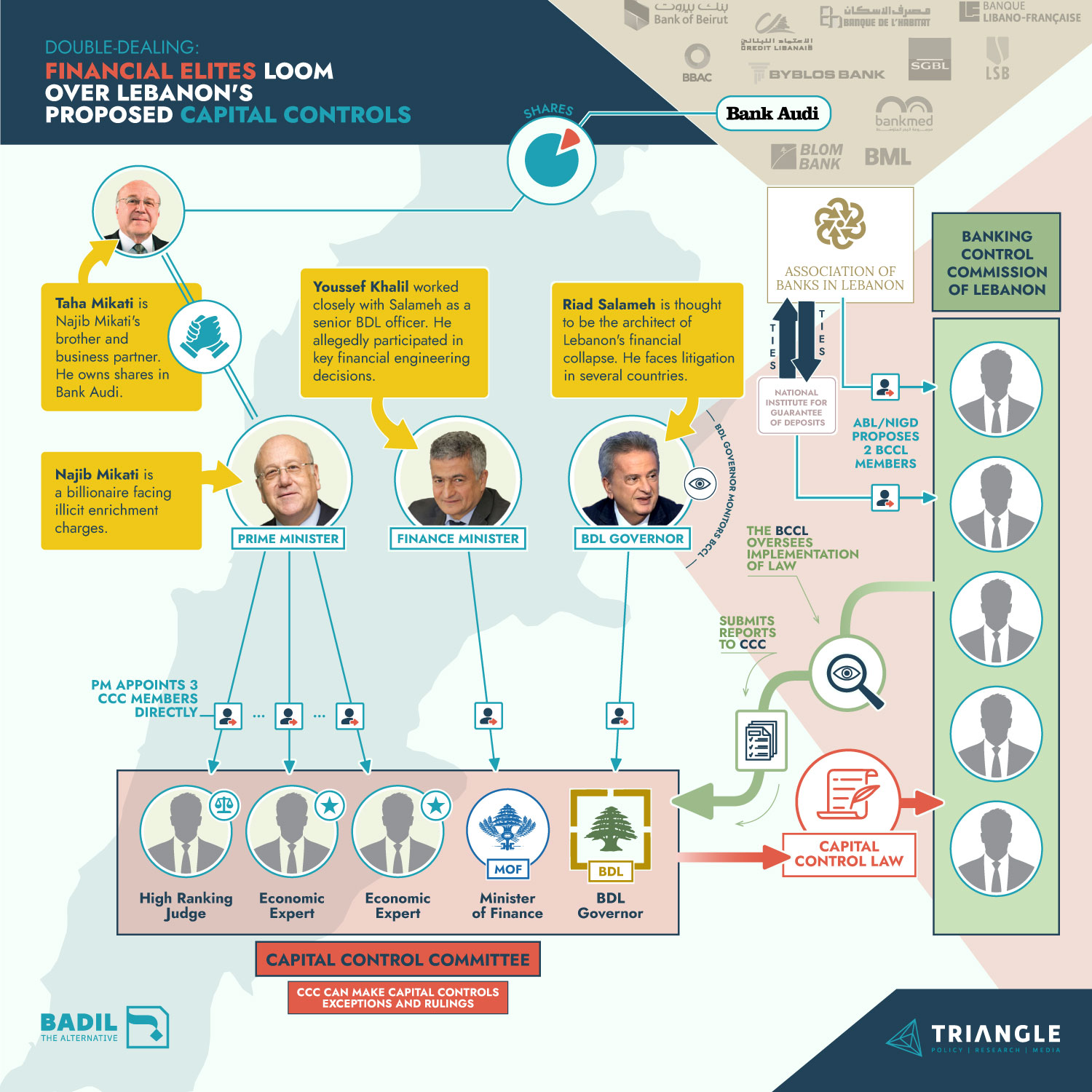

The earlier draft appointed four members to the newly formed Capital Controls Committee (CCC), which is responsible for making amendments to the law, rulings on exceptions, and submitting quarterly reports to the Cabinet. These committee members were to be the Prime Minister, the BDL governor, the Minister of Finance, and the Minister of Economy & Trade. Critics pointed out that such a composition would only enshrine the politico-banking class’ leadership over the country’s capital controls.

At present, for instance, doubt swirls over at least three of these public officeholders. BDL governor Riad Salameh is widely considered to be the architect of Lebanon’s financial collapse and faces corruption and embezzlement charges in several countries. Finance Minister Youssef Khalil worked as a senior BDL officer, where he allegedly worked closely with Salameh and participated in key financial engineering decisions. And, for his part, current Prime Minister Najib Mikati is facing his own illicit enrichment charges, alongside Bank Audi. Mikati’s brother and business partner, Taha Mikati, owns shares in the same bank.

Following the public backlash, the latest draft replaced the Prime Minister and Minister of Economy & Trade with two economic experts and a high-ranking judge. Yet the Prime Minister would be responsible for appointing all three figures, ensuring that the premier retained indirect influence over the CCC’s operations. At the same time, the amended CCC membership still includes BDL governor Salameh and Finance Minister Khalil, despite their alleged personal culpability for Lebanon’s collapse.

For regulatory oversight, the capital controls regime would rely on the five-member Banking Control Commission of Lebanon (BCCL), another compromised institution. Under Article 10 of the proposed capital control law, the BCCL would be responsible for monitoring the law’s implementation and reporting violations by Lebanese banks.[ii] However, the Association of Banks in Lebanon (ABL) always nominates one BCCL member. ABL also wields power over a second BCCL nominee – formally made by the National Institute of Guarantee for Deposits (NIGD) – given that ABL holds a majority stake in NIGD’s management.[iii]

On top of being influenced by ABL, BDL notes that the BCCL always works in close coordination with the BDL governor, even though the BCCL is meant to enjoy institutional independence.[iv] In this sense, the proposed system’s watchdog would arguably be compromised by both BDL and Lebanon’s commercial banks – both of which could lose heavily from fair implementation of capital controls.

In with the old, in with the new

Institutional bias at the CCC and BCCL threatens to skew the crucial rules surrounding “fresh” and “old” money in the Lebanese economy. As with the previous version, the latest draft law proposes to codify the distinction, which already exists informally under the illegal capital controls regime. The latest draft defines “old” money deposits as those transferred or deposited into a given Lebanese account before 9 April 2020. The legislation does not, however, provide comprehensive rules for how this money should be treated.

Similar ambiguity besets other key issues under the draft legislation. In one notable example, the law would allow depositors to withdraw up to US$1,000 per month in either foreign currency, Lira, or both. Yet the law does not specify which currency the depositor should receive their money in; instead, it allows the CCC to make this determination.

To date, Lebanon’s banks have generally preferred to short-change depositors making withdrawals. In past months, commercial banks have allowed depositors to withdraw up to US$750 per month, at the approximate rate of 8,000 LBP. At the time of writing, the black-market rate stands at around 25,000 LBP. Accordingly, withdrawals at the 8,000 LBP rate force depositors to accept haircuts of more than two-thirds on their savings’ true value.

The compromised CCC would also enjoy broad discretion to determine exemptions under the capital controls regime. The legislation explicitly identifies various categories of exemptions, which include transfers abroad for imports, exports, healthcare costs, and tuition fees. For each category, ambiguity reigns supreme.

Mohamad Faour, Assistant Professor of Finance at the American University of Beirut, offered the example of how the draft capital control law does not distinguish between what the necessary imports are. His worry is that “we are reproducing another channel through which politicly connected importers are going to benefit from the system via a face-value capital control law,” similar to what happened during Hasan Diab’s government with the subsidized package of goods. CCC would determine when and how funds could be unlocked, without serious regulatory procedures in place.

Crucially, the draft law empowers the CCC to grant capital controls exemptions for any other matter deemed worthy by the committee. This “catch-all” provision grants the CCC ample room to make concessions unrelated to the capital controls law’s specific exemption categories, introducing a codified, arbitrary way out for privileged depositors.

“Get out of jail free” card

Most alarmingly, the draft legislation would grant a sweeping immunity to Lebanon’s banking sector concerning the illegal capital controls imposed since October 2019. Article 12 of the draft law explicitly states that immunity applies “to all judicial procedures of any kind as well as lawsuits filed or to be filed against banks and financial institutions… whatever the location or nature of those lawsuits.”[v]

Under this broad provision, the capital control bill purports to shield banks retroactively from all ongoing and future litigation, both in local and foreign jurisdictions. Despite Lebanese banks having unlawfully denied depositors from dealing with their savings for years, the amnesty clause absolves those same banks from any obligation to pay compensation.

Already, depositors have successfully established legal claims against Lebanese banks, both within Lebanon and abroad. The immunity clause would subvert the course of justice through these various court systems, allowing Lebanese banks to escape liability for unlawfully defending their own financial interests at their customers’ expense.

More of the same?

While Lebanon’s depositors may have temporarily avoided this flawed version of capital controls, the issue will resurface on Tuesday 19 April for special parliamentary committee discussion. The IMF’s “staff-level agreement” with the Lebanese government, which was announced last Thursday, makes any financial rescue package conditional on implementing a capital control law. [vi]

The legislation’s troubled history indicates that the country’s politico-banking elites have not abandoned the proposed law’s most egregious terms. It would not be surprising, for instance, to see other immunity clause inserted in possible future drafts, despite widespread public denouncement.

Lebanon can benefit from enacting a fair, transparent set of rules for imposing capital controls. Such legislation would provide a more even playing field for Lebanese depositors, as opposed to the continued application of arbitrary, hopelessly biased, and unregulated informal restrictions.

Yet the Lebanese public should not accept any capital controls law that would assign control of the resulting system to decision-makers holding deep-rooted conflicts of interest with the banking sector. Under the latest draft, all sitting members of the CCC – not to mention at least two BCCL officials – arguably fail this basic test of fitness for office.

Naturally, a proper law will not grant legal immunity to Lebanese banks for the illegal capital controls regime – sustained financial misconduct for which there must be accountability. Ideally, the eventual capital controls legislation will provide clearer rules on accessing “old” money deposits, which the latest draft left to the CCC’s discretion.

Most ordinary Lebanese would welcome any step that could help usher in a brighter future, including a proper capital controls law. But they cannot yield – as the country’s elites hope that they will – to restrictions that will further deplete their savings to absolve the sins of the few.

[i] Cry of the Depositors, April 14, 2020

[ii] Draft Capital Control Law, “Minutes of The Cabinet”, March 30, 2022, Seen by Triangle

[iii] Hicham Safieddine, The Legal Agenda, May 22, 2020, “The Lebanese Banking Troika: A History of Instability and Unilateral Decision-Making”, Online at: https://bit.ly/3JBj2GF

[iv] BDL Organization Chart, https://www.bdl.gov.lb/tabs/index/1/285/BDL-Organization-Chart.html

[v] Draft Capital Control Law, “Minutes of The Cabinet”, March 30, 2022, Seen by Triangle

[vi] IMF Press Release, International Monetary Fund, April 07, 2022, https://bit.ly/3EcFG7b