In these first days of what is being hailed as a “new era” in Syria, the authorities now controlling Damascus are sending mixed signals. On one hand, they are voicing their commitment to preserving Syria’s state institutions, and respecting the diversity of its population. On the other hand, however, they are signalling an intention to monopolise the highly delicate process of political transition, and consequently state power.

The path they eventually choose to follow will determine whether the mistakes and miscalculations that devastated not only al-Assad’s Syria but also Iraq and Lebanon will be repeated here in this “new era”.

Before Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS) forces under the command of General Ahmed al-Sharaa, AKA Abu Mohammed al-Julani, entered Damascus on December 8, they pledged to maintain the formal structure of the country’s institutions. Former Prime Minister Mohammed al-Jalali formally remained in office until December 10 and played at least a cosmetic role in the handover to Mohammed al-Bashir, the transitional prime minister who is set to serve in this role until March.

Shortly before this, the HTS forces also announced a general amnesty for soldiers of the Syrian army, signalling their intention to preserve the regular military, which is a central pillar of the state.

Preserving the structure and unity of the military institution is key to preventing state collapse during a political transition. We have seen the disastrous consequences of failing to do so in Iraq, in 2003. In fact, Iraq is still suffering the consequences of this grave mistake today, more than 20 years after the destruction of its military organ during the invasion.

The HTS authorities have also demonstrated no interest, at least so far, in initiating an intense de-Baatification process akin to the one that hollowed out all of Iraq’s institutions and destabilised the country for decades after the fall of Saddam. For all intents and purposes, it looks like the new authorities are not planning to target the Baath Party, which has been in power in Damascus since 1963, as an institution. The leadership of the former single party announced a suspension of activities, but not their cessation. The party’s website is still operational – featuring a photo of Bashar al-Assad no less – and its central and local offices have not been systematically attacked, as one might have expected in the aftermath of regime change.

In other positive signs, Interim Prime Minister al-Bashir declared that the incoming government intends to dissolve the oppressive security agencies that, since the 1960s, have terrorised millions of Syrians. He announced plans to repeal the so-called “anti-terrorism laws,” which came into effect in 2012 as a revamped version of special laws that, for more than 50 years, legitimised military tribunals targeting hundreds of thousands of activists and dissidents.

These are undeniably positive steps, many of which reflect a desire to build a new Syria without dismantling the core elements that make possible its survival as a state. The interactions of the incoming authorities with citizens at the municipality level, which have so far marked by an emphasis on civil – not military – relations also signal a constructive approach to governance.

However, all these promising signs are somewhat overshadowed by moves and statements by the incoming authorities that carry echoes of Syria’s authoritarian past, which may lead the country to repeat the mistakes its neighbours made during their own political transitions.

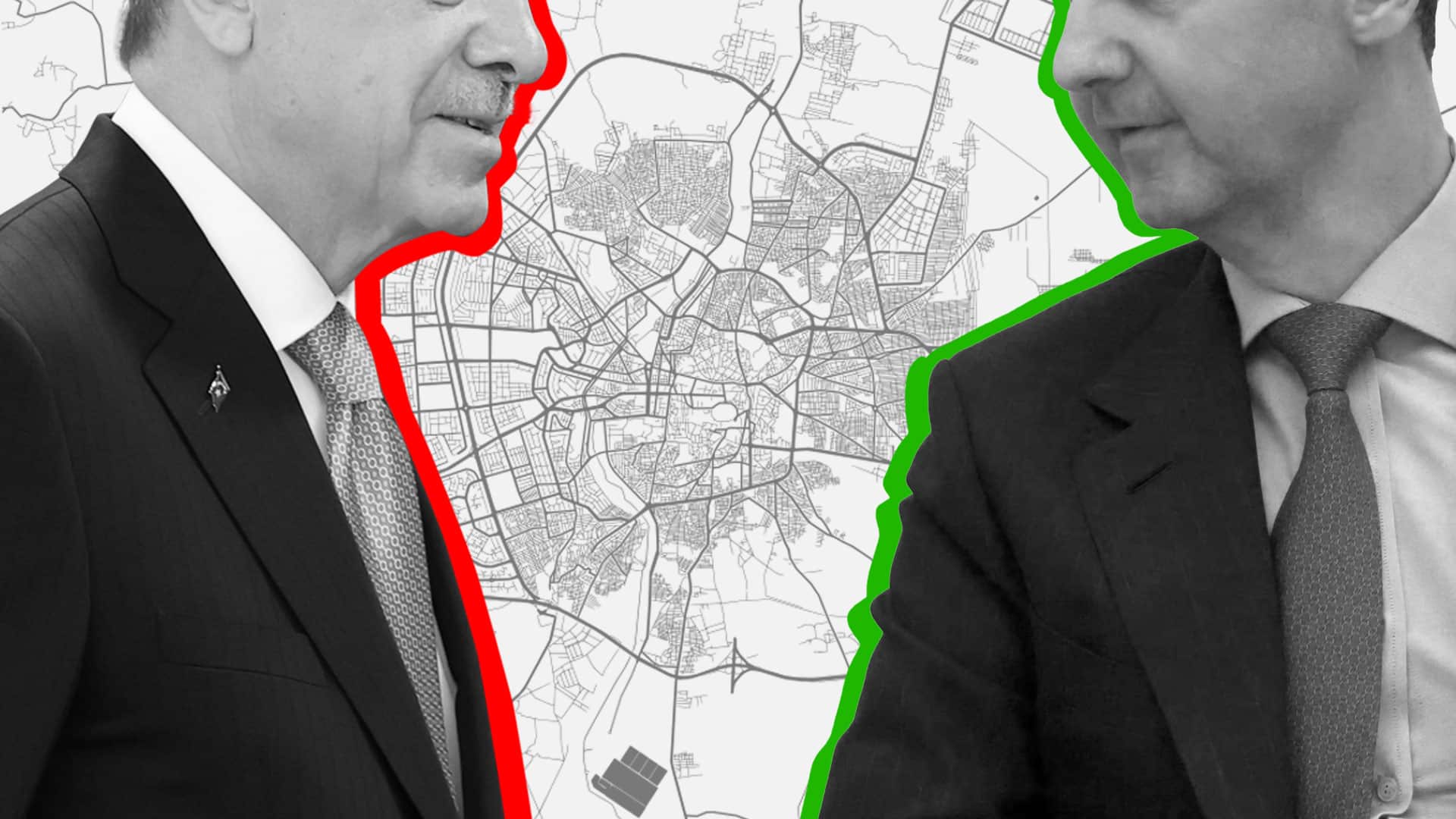

HTS leader al-Sharaa, for example, announced the appointment of al-Bashir, who previously led the so-called Salvation Government of Idlib, as prime minister without consulting any forces outside of the group. This appointment, made unilaterally and based solely on in-group ties, has made people worry the dysfunctional power mechanisms of al-Assad’s Syria may continue into the new era.

Another striking development was the decision to display the HTS flag – featuring the Islamic profession of faith (shahada) in black on a white background – during the first meeting of the new government, held in the prime minister’s office. To many, this was reminiscent of how, until a few days ago, the Syrian tricolour was always accompanied by the banner of al-Assad’s Baath Party.

Less surprising, but no less significant, has been the implicit contradiction between the new authorities’ media declarations about the inclusivity of their state-building project and their silence regarding the inclusion of Kurdish-Syrian communities. Al-Sharaa and his inner circle appear unwilling to embrace Kurds and invite them to take part in this national project while delicate negotiations over power balances along the Euphrates are under way between Turkiye, which supports HTS, and the United States, which maintains a military presence in Kurdish-controlled areas. Furthermore, opening up to the Kurds could risk antagonising Turkiye, whom the new leaders in Damascus likely see as crucial to maintaining the support of if their fledging governance project is to succeed.