Executive Summary

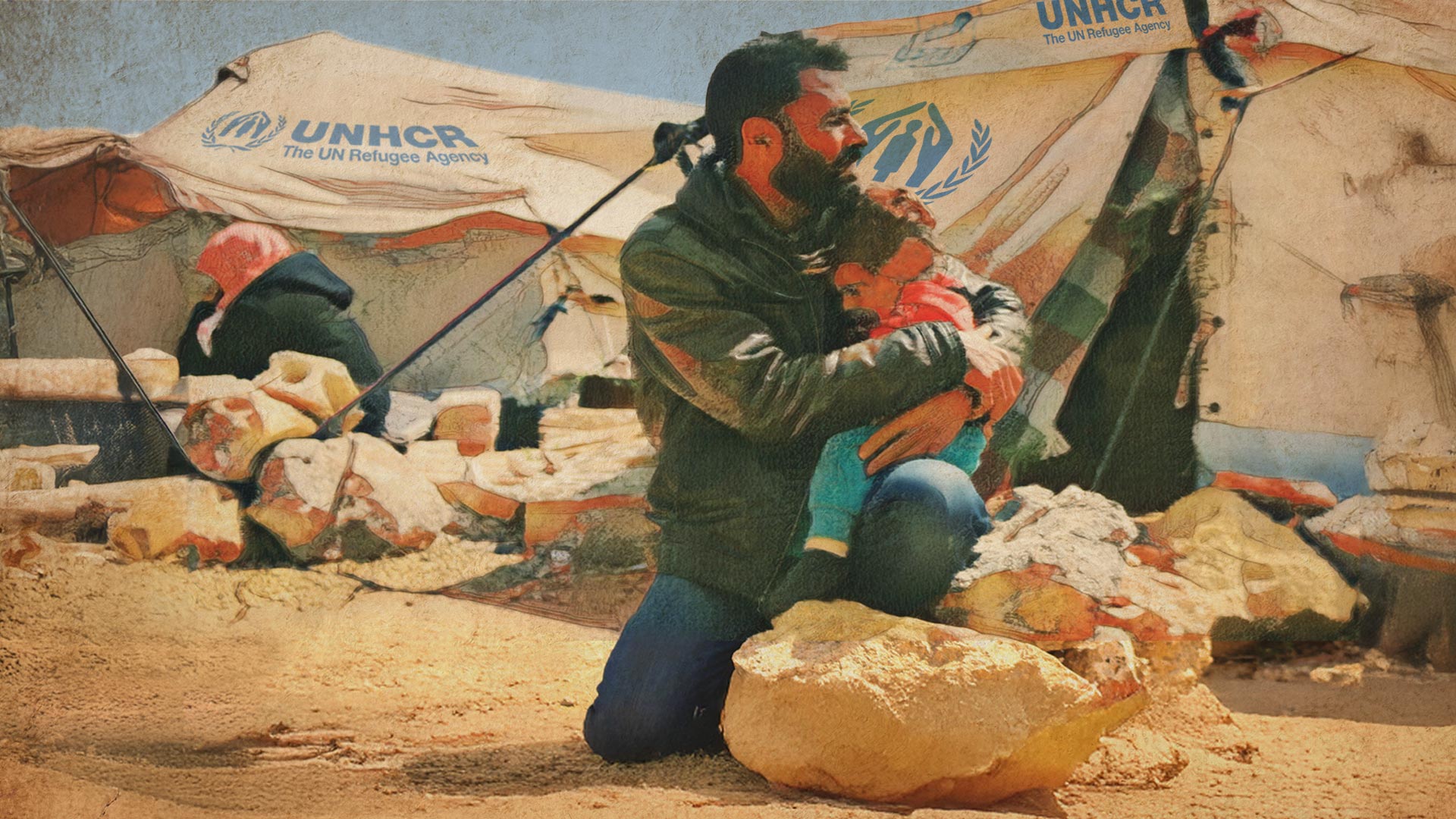

Syria has suddenly become a haven of safety, or so it would seem if one listened to recent Lebanese political rhetoric. Leaders from various sides in Lebanon’s fractious political landscape have coalesced around this narrative shift since mid-September, when Israel’s ongoing military escalation led to almost 350,000 Syrian refugees in the country fleeing back across the border into Syria. The reality, however, contrasts starkly: Human Rights Watch recently documented that refugee returnees face “the blatant risk of arbitrary detention, abuse, and persecution.”

Why, then, Lebanese politicians’ escalated praise of security and safety on the Syrian side of the border? As this paper will show, it is the latest cynical manifestation of their years-long campaign against Lebanon’s Syrian refugee population, one that has denigrated and dehumanised these refugees, including scapegoating, marginalisation, and violence, for Lebanese leaders’ political expediency.

The still-unfinished Syrian civil war, which began in 2011, had led to some 1.5 million Syrian refugees fleeing to Lebanon. After Lebanon entered economic collapse in 2019, Lebanese politicians’ vitriolic attacks against this population became acute. This appears to have been a concerted campaign to deflect blame from the political class and to focus the public’s anger elsewhere. While local and international media have previously suggested this was the case, these claims had not been backed by empirical data – until now.

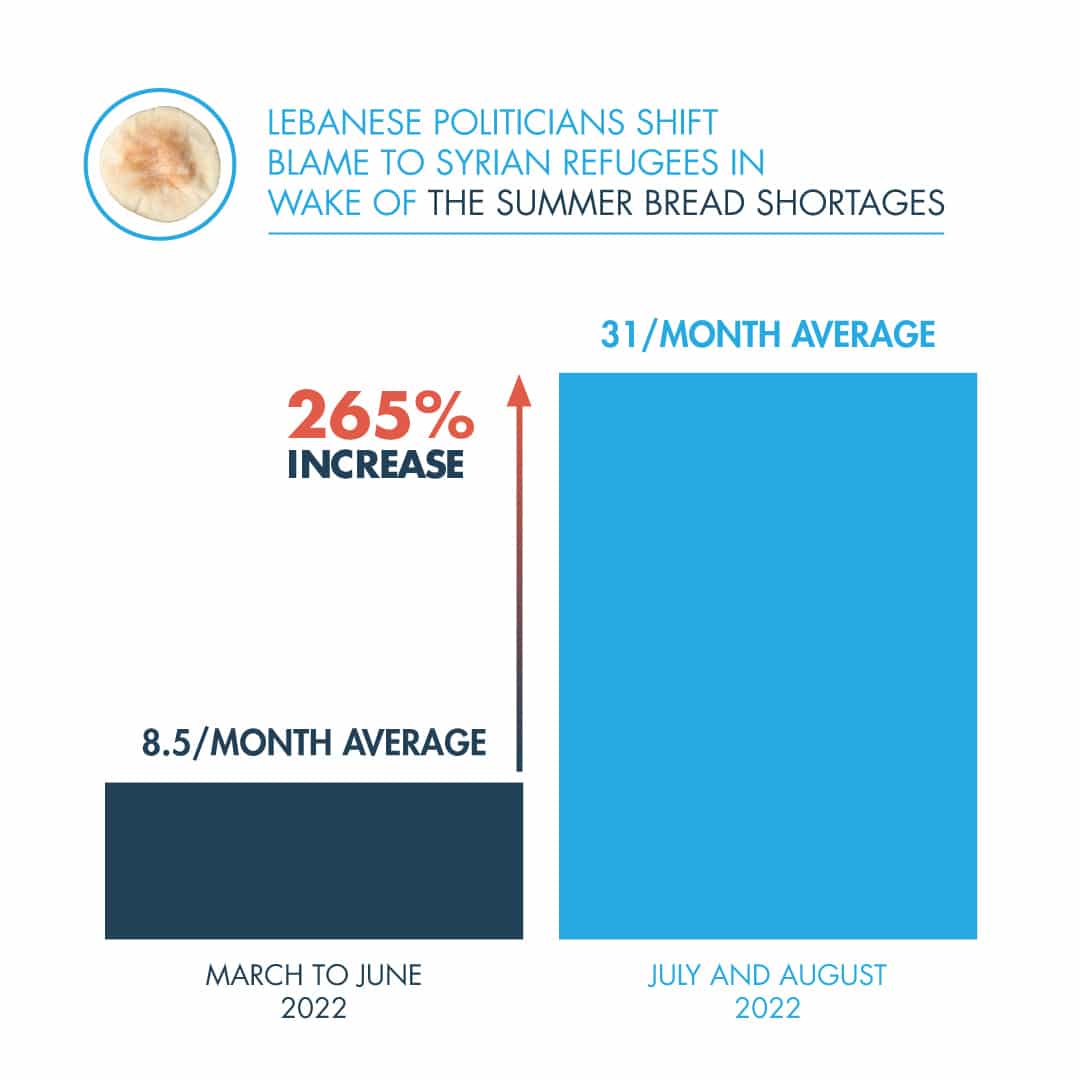

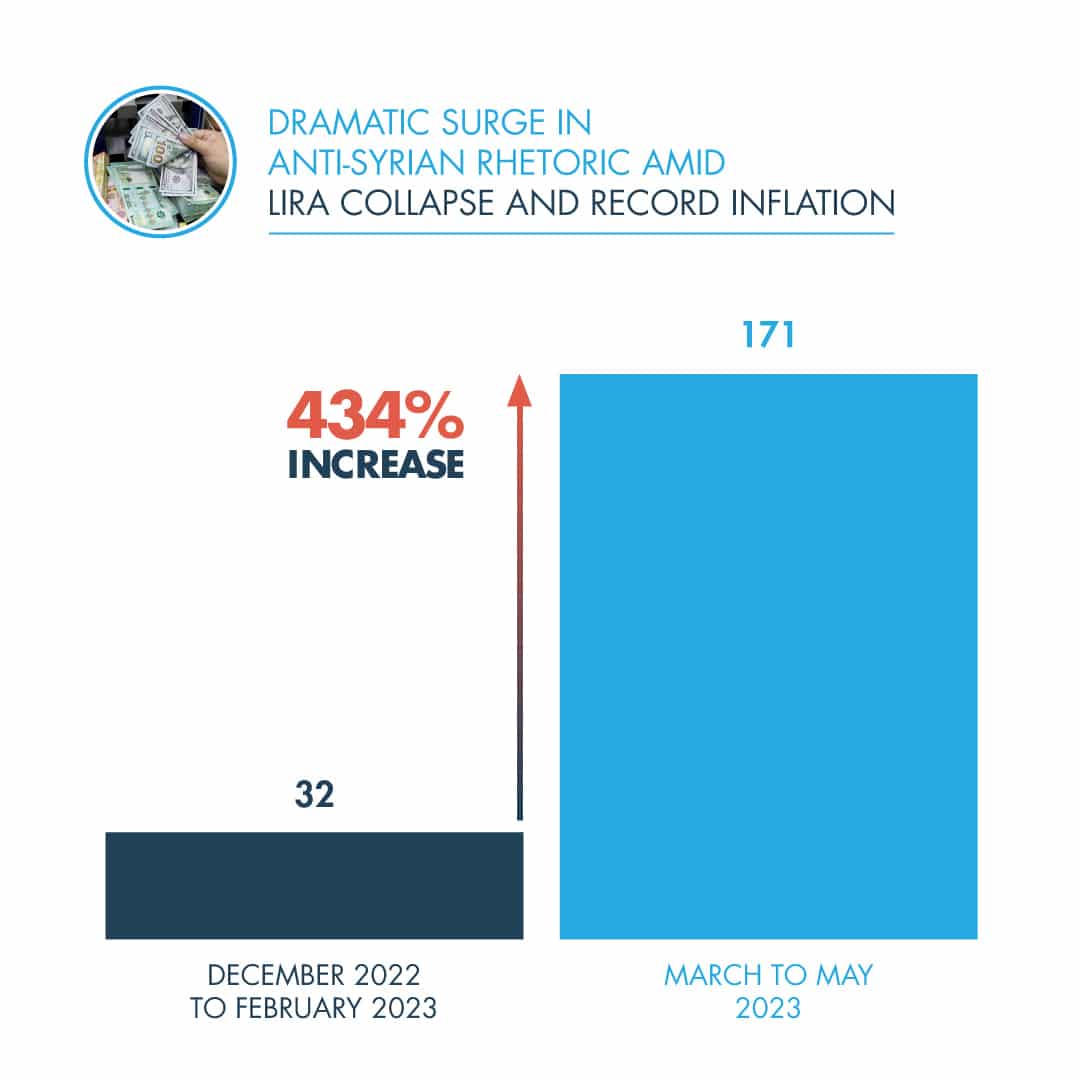

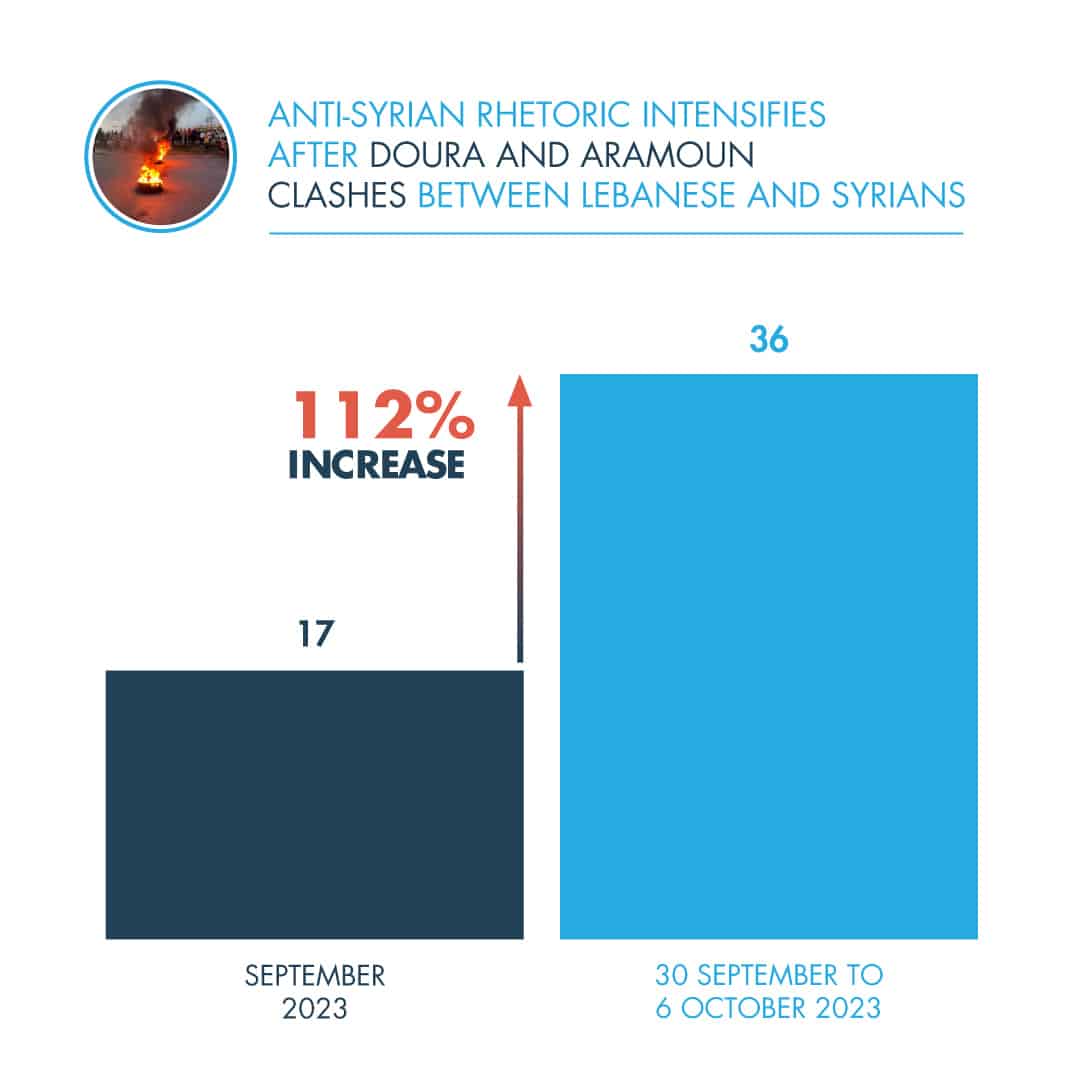

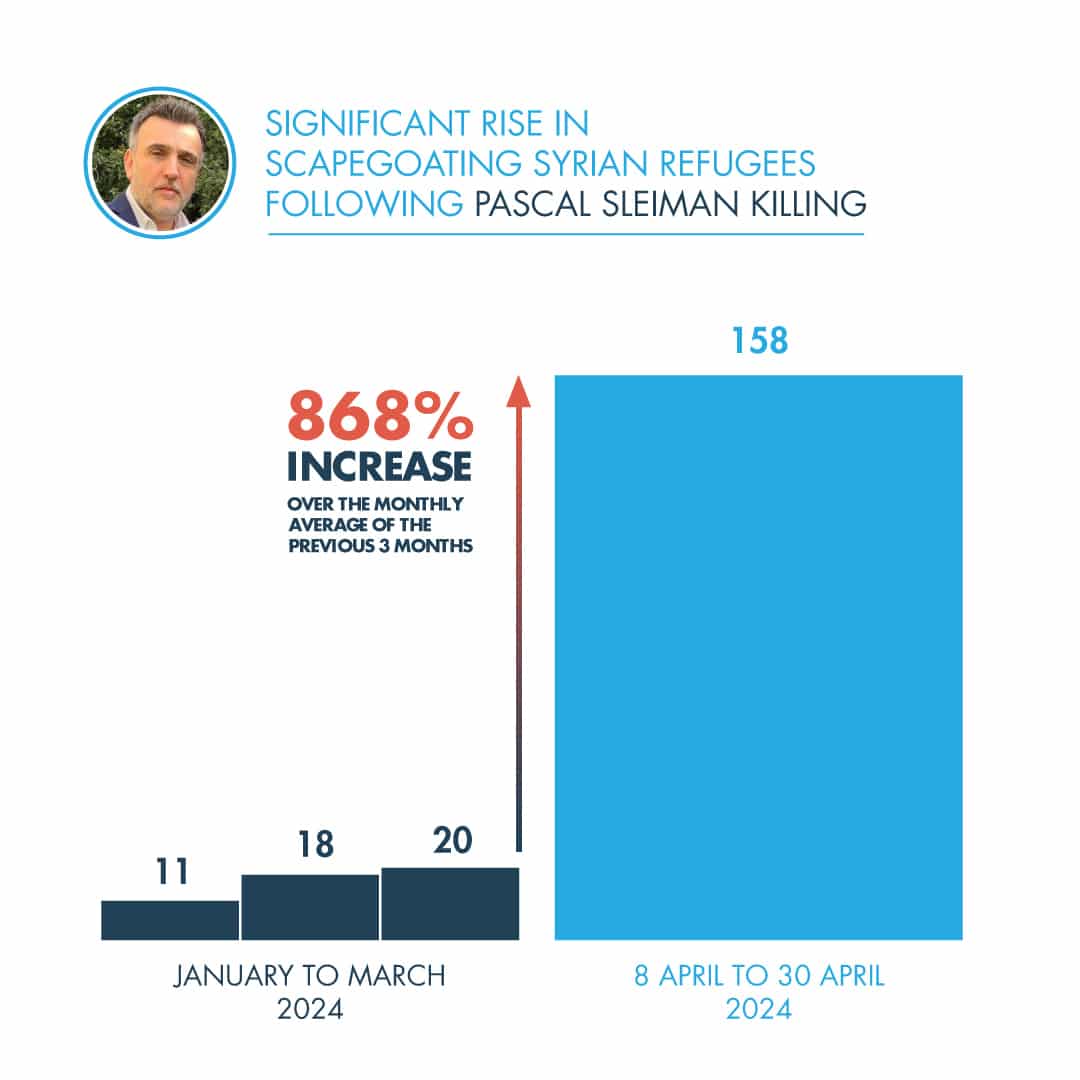

Over the past two and a half years, Badil has tracked what Lebanon’s leaders say across print and social media. Our monitoring has shown repeated instances where spikes in political and economic instability within the country have coincided with an uptick in anti-Syrian rhetoric, suggesting a deliberate strategy of blame-shifting. Since the Israeli military escalation in mid-September, this narrative has morphed from castigating the refugees to framing the fact that some have returned as a signal that Syria is now safe for all to go back.

Numerous rhetorical examples exist from members of the Lebanese government and political elite. These include Lebanon’s Minister of Social Affairs, Hector Hajjar, suggesting that conditions in Syria might now be safer than those in Lebanon; Free Patriotic Movement (FPM) MP Gebran Bassil, who framed the wave of displacement as an opportunity for Syrians to return; and Lebanese Forces (LF) leader Samir Geagea, who asserted that the return of refugees proves there are safe areas in Syria. These assertions are, however, both misleading and dangerous: Syria remains an ocean of violence and persecution, not an oasis from such.

Lebanese politicians’ current rhetorical line hasn’t wholly divorced itself from the previous pattern of denigration – Syrian refugees, for example, have been blamed for being agents to Israel and unsanitary vectors for contagious disease spread. As well, the new narrative framing will likely continue to engender the hostility of the previous one, creating even greater unsafety for the hundreds of thousands of Syrian refugees who remain in Lebanon and adding more dry wood to a social tinderbox.

The Badil Media Monitoring Database: Tracking the Blame Game

Before the Israeli military escalation against Lebanon in mid-September, the fractious Lebanese elite could agree on little. Among the few points on which they and their propagandists did find common ground, however, was that the country’s Syrian refugees were to be blamed for almost everything – from rising petty crime, outbreaks of violence and bread shortages. Numerous reports and studies had shown these claims to be patently and demonstrably false. Adhering to the truth, however, has rarely been a concern of the Lebanese elite. What interests them is maintaining support within their sectarian constituencies and, thereby, their domain over the power centres within the state apparatuses through which they plunder the public wealth.

Years before the ongoing war in Lebanon erupted, the political and banking elite’s greed had driven the country into one of the worst economic crises in modern history, causing the currency to collapse 98 percent in value and banks to withhold life savings from millions of people. The elites’ survival was predicated on having blame focused elsewhere, and there could be no better target for such scapegoating than the roughly 1.5 million Syrian refugees who had been residing in Lebanon. Latent social prejudices against Syrians provided the coals to build the fire, while the refugees themselves lived largely in social and economic precarity with little recourse to legal protections nor the ability to mount a public defence.

This public maligning of Syrians found unfortunate resonance with segments of the Lebanese population. Anti-Syrian incitement at the community level was used to justify repressive policies against the Syrian refugee community and gave carte blanche to mob violence. By collectively branding all Syrians either as a security threat or the driving force behind the country’s successive calamities, the political class rallied nationalistic sentiments to justify stringent anti-Syrian security measures. These included prohibitive Lebanese laws that excluded Syrians from working in most sectors and accessing healthcare, as well as restricting their freedom of movement within Lebanon.